Quinn Dombrowski

(On Saturday the 18th of January, Dr Chris Kaishin Hoff, an Empty Moon Zen Senior Dharma Teacher delivered the talk. With his generous permission I’m reprinting it here. I find it particularly timely…)

In December, the counseling clinic I direct had a Secret Santa gift exchange. When it came my turn to open a gift, I was surprised by a coffee mug with the phrase “hope betrays” printed on it. I laughed out loud. You see, all the therapists who work for me have had to hear me regularly say that “hope betrays.” Many people who seek help at our counseling center are confronting challenges because of hope—hope for change by someone else for example, someone they have no control over. I also use this phrase as a reminder not to fall victim to an unhelpful positivity by putting a positive spin on the very real problems people are contending with when they sit with us.

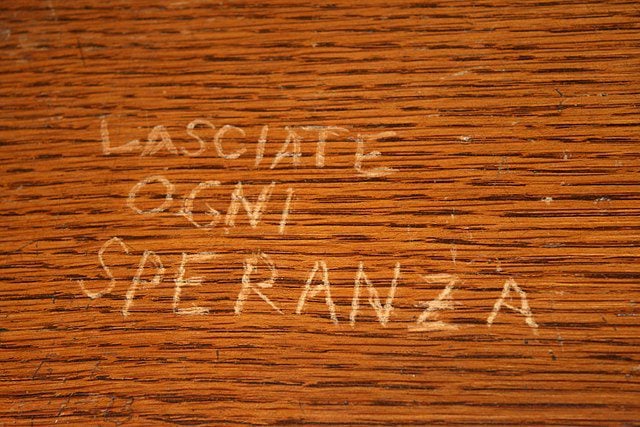

Zen and Buddhism in general hasn’t been too enamored with hope either. For example, Pema Chodron once said, abandoning hope is an affirmation, the beginning of the beginning. You could even put abandon hope on your refrigerator door instead of more conventional aspirations like Every day in every way I’m getting better and better. In her book When Things Fall Apart, she critiques the concept of hope as a form of clinging. In her view, hope can create a subtle resistance to the present, and by letting it go, we find greater freedom.

In Zen, hope can be considered something extra. Not necessary. Zen suggests that the transformative power of life comes from being fully present in the moment, beyond the dualities of hope and despair or any other distractions that pull us from our life as it is, right now.

But lately I have been reexamining hope. And maybe I need to rename it. Like contemporary Zen teacher Roshi Joan Halifax has done. In her work on end-of-life care and social activism, she often discusses a wise hope. She suggests the need for a hope that is not attached to specific outcomes but is grounded in compassionate action. She says, Wise hope is not seeing things unrealistically but rather seeing things as they are, including the truth of suffering—both its existence and our capacity to transform it. Halifax’s wise hope aligns with Zen’s emphasis on clear seeing and non-attachment, fostering a hope that supports engagement without delusion.

But what I have discovered is that hope does not lay down easy. This persistence hints at the irrepressible nature of hope, which can persist even in the most hopeless-seeming conditions. This might reflect something fundamental about us messy humans—a yearning for connection, growth, or renewal that refuses to be extinguished. Perhaps this is why, even in Zen, hope is not entirely dismissed but rather reimagined. It is not about erasing hope but transforming it into something wiser, freer, and less entangled.

So how do we tangle with hope? An important question in contemporary times. Recently I read something the musician Nick Cave had written on hope.

Cave offers us an intriguing perspective on hope. In Faith, Hope and Carnage, he writes: Hope is optimism with a broken heart. This means that hope has an earned understanding of the sorrowful or corrupted nature of things, yet it rises to attend to the world even still. We understand that our demoralisation becomes the most serious impediment to bettering the world. In its active form, hope is a supreme gesture of love, a radical and audacious duty, whereas despair is a stagnant rejection of life itself.

I think Nick Cave’s words resonate deeply with Zen practice. The idea of optimism with a broken heart captures something essential about Great Faith, Great Doubt, and Great Energy—three pillars of Zen. Great Faith isn’t naive optimism; it’s the willingness to step forward even when we understand the impermanence and suffering that permeate life. It is the trust that this path, even in its uncertainty, will lead to awakening.

Here, I’d like to invite you to reflect on a moment in your life when you experienced Great Faith. Perhaps it was a time when the way forward seemed unclear, but something within you—a quiet, steady resolve—kept you moving forward. Pushed you across the threshold. For me, If I were to look back honestly, my life is filled with moments of Great Faith. From my entry into recovery, to a mid-life career change to follow through on my wish to become a therapist, and through several experiences of getting on the other side of that preverbal dark night of the soul, journeys I don’t believe anybody escapes. Moments like these reveals how Great Faith isn’t about certainty; it’s about trust.

Great Doubt is the second pillar, and it tempers Great Faith. It’s the willingness to sit with uncertainty, to confront the sorrowful and corrupted nature of things without flinching. In Zen, doubt is not a rejection of faith but a necessary companion to it. It keeps us honest. When we cling to hope as an outcome—If I do this, things will get better—we are trapped in a dualistic mind. Great Doubt dismantles this grasping, allowing us to meet life as it is.

I don’t think anybody who has begun a Zen practice hasn’t had the experience when doubt has overwhelmed them. Many a time I’ve sat on the cushion wondering, “Why am I doing this? What’s the point?” Yet, rather than walking away, I leaned into the doubt, exploring it as if it were a koan. What is this doubt pointing to? What does it mean to truly not know? If you’ve had a similar experience, I encourage you to think about how Great Doubt has shown up in your life and what it has taught you.

And then there is Great Energy. Great Energy is what animates our practice. It’s the supreme gesture of love that Nick Cave speaks of. It is what allows us to show up, again and again, despite heartbreak, despite disillusionment, despite knowing the impermanence of all things. It’s the audacious duty of attending to the world, not because we believe we can fix it, but because engaging with it is itself a radical act of love. It is the practice.

Great Energy reminds me of the story of the bodhisattva who vows to save all beings, even knowing it is an impossible task. Why would anyone take such a vow? Because the act of engaging with suffering—of meeting it with an open heart—is transformative in itself. For me, Great Energy often shows up in small, quiet ways: the decision to sit zazen even when I’d rather sleep in, or the effort to truly listen to someone in pain without offering easy answers. These moments, though small, are powerful. And when the world seems at its darkest, when it seems to be spiraling out of control, Great Energy is the remembering that I direct a community counseling center. Where people who couldn’t access mental and relational health services have found help. Showing up there, with energy, and doing all the small things required right sizes my world again and I am no longer overwhelmed.

In this way, I wonder if Zen does not ask us to abandon hope entirely, but to abandon hope as we commonly understand it—as a wish for a specific outcome, as a tether to what we cannot control. Instead, Zen invites us to embody a deeper, more courageous form of hope: hope with a broken heart, hope tempered by Great Doubt, and hope that fuels Great Energy.

As we sit this January, confronting all the challenges of our current moment how might we reflect on the ways we can realize these qualities in our practice and in our lives. How can we hold Great Faith in the path, even as we allow Great Doubt to strip away our attachments? How can we cultivate Great Energy to meet the world as it is, not as we wish it to be? And perhaps most importantly, how can we extend this practice outward, transforming hope from a wish into a radical act of care for the world?

Late last year I had a book come out that I was co-editor on titled An Encyclopedia of Radical Helping. The Encyclopedia is a collection of interconnected entries on helping and healing by over 200 contributors from all over the world. One of my favorite contributions was written by my co-editors and friends Erin Segal and Julie Cho. In it they explore the concept of ongoingness. Ongoingness is the practice of letting go of hero narratives—the idea that liberation or change is achieved through singular, dramatic acts—and instead focusing on the everyday, collaborative, or interconnected efforts that sustain us. They remind us that ease often leads to more action and that even rest can be a form of resistance. Ongoingness reframes liberation as part of a larger story—one that began before us and will continue after us. It emphasizes care, connection, and the long view over quick fixes or final victories.

In Zen, this perspective aligns beautifully with our focus on the present moment. The practice of ongoingness invites us to show up with Great Faith, Great Doubt, and Great Energy—not for an imagined endpoint, but because the ongoingness itself is the practice. When we shift our understanding of hope to one of ongoingness, it becomes less about yearning for a specific outcome and more about engaging with life as it unfolds. This is the radical heart of Zen: meeting each moment fully, without clinging, and recognizing that the act of showing up is itself transformative.

Let us meet the new year not with shallow optimism or deep despair, but with the profound clarity and compassion that Zen practice cultivates. In this way, perhaps hope need not betray us after all.