EGYPT

1851

“Forty years have I before me in which to build a more enduring fame that that of the builder of the Great Pyramid,” Blavatsky told Countess Kazenova. It was 1851, and the women were sitting in a room in Cairo, in Samuel Shepheard’s Hotel des Anglais. “Who was he anyway?” Blavatsky continued. “Only a name, an oppressor of his fellow men. I will bless mankind by freeing them from mental bondage.”

“That is sublime Helene,” replied the countess, “but how do you propose to go about this little task?”

“I know I was intended to do a great work. What it is to be, I know not, but great it will be, and known to the world as a blessing to all except to priests.”

“Is your visit to Egypt a part of your plan?”

“I have no plan. No. I came here with a friend merely to see the relics of the oldest civilization to come out of India. Here I find much to study, and have been busy some days at Old Cairo, assisted by an American artist studying the ways of the serpent charmers.”

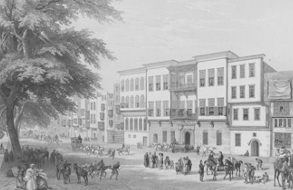

Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo.[1]

Egypt had been a part of the Ottoman Empire since 1517. Around the time of the Napoleonic Wars (1804-1815) a junior officer in the Ottoman army, a Balkan Turk named Muhammad Ali, was dispatched to Egypt to fight the French. After the Ottoman victory, a chaotic power vacuum was created in Egypt. Muhammad Ali successfully quelled the uprisings, and the Ottoman Sultan named him Wāli (governor) of Egypt in 1805. Muhammad Ali had loftier ambitions and assumed the title of Khedive (Viceroy,) of a government he called the Khedivate of Egypt. The Ottomans tolerated this (though they did not officially recognize the title.) Ali would implement revolutionary reforms that brought Egypt into closer contact with the mercantile and state actors of the West. Tensions between the Khedive and the Sultan grew, ultimately resulting in armed conflict. Ali’s army defeated the Sultan’s army in two major campaigns, and the ruler of the Ottomans conferred upon Muhammad Ali the recognition of a hereditary right to rule Egypt and Sudan. Egypt was effectively a semi-autonomous country within the Ottoman Empire.[2]

In 1819 the Khedive invaded Sudan and heavily taxed the annexed people under the ensuing colonial system. Having learned something of the European’s conception of Egypt (and their fascination with its history) Ali borrowed heavily from the symbolism of Egypt’s ancient past. He did this to further impress upon the minds of potential allies that the history of his land extended long into the forgotten past, that is, before the Ottomans and the Europeans. Muhammed Ali became the first to borrow Egypt’s mythic vocabulary for use on official state records. His efforts proved successful, and soon European powers (British and French) worked with Egyptian authorities for a proposed Suez Canal, a project that would allow European powers to avoid sailing around Africa to reach India.[3]

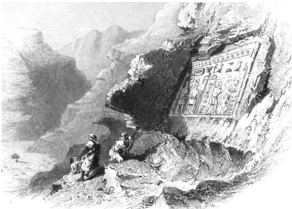

Egyptian Ruins.[4]

Blavatsky picked up smoking hashish in Cairo with her American artist friend, twenty-two-year-old, Albert Leighton Rawson, of Chester, Vermont. The son of a New York hotel keeper, Rawson was educated by a private tutor from Oxford University, who went on to study law. After university, he explored the “Indian mounds of the Mississippi Valley” and visited Central America.

“Hashish multiplies one’s life a thousandfold. My experiences are as real as if they were ordinary events of actual life,” said Blavatsky. “My most precious thoughts come to me in my smoking hours. My mind is then tranquil, and I feel lifted from the earth and I close my eyes and float on and on anywhere or wherever I wish. Ah! I have the explanation. It is a recollection of my former existences my previous incarnations. It is a wonderful drug, and it clears up a profound mystery.”

“What a crowded memory we should have if the incidents of a few thousand previous incarnations should return at once.”

“Eejut! Only one series can by any possibility be in the mind at a given time. But suppose…ah! Only think if some of those incarnations had been in a brute or a reptile. Then what would the sensations be?”

“A philosophic scheme to hold an ignorant people in bondage with; such a people as we suppose the Egyptians were.”

“The higher the degree of education the more terror such an idea would have. The farmer’s boy in the parable of the prodigal son was glad to share with the pigs; but what would a young fellow fresh from Columbia College think about such a situation? If it is not true, it ought to be. How is the rascal, rich and successful in life, an oppressor of numberless victims, ever to be paid off for his evil deeds, if he can’t be put to service as an omnibus horse or a mule, or entombed in a snake’s body, hated, and shunned by all, slimy, venomous, hiding from the light of day, with no weapon except its villainous mouth.”

Cairo.[5]

In 1851 Rawson made a pilgrimage to Mecca disguised as an Egyptian native. a “trick” he employed on several occasions.[6] Both Blavatsky and Rawson would go about Cairo disguised as Muslims to avoid harassment from the crowd. Any persons in European dress were sure to be molested as “hated infidels,” if not outright murdered. Locals had grown weary and suspicious of outsiders. In recent years there was a widespread belief in England, Germany, and America, that the Millennium, a thousand-year reign of Jesus and his followers, was soon at hand. This impulse in the Christian West inspired what was termed a “peaceful crusade” in the Holy Land, “[to] liberate Palestine from the Muslim infidels,” through “philanthropic activities.”[7] Missionary activities flourished in the 1830s when the Egyptian Khedive, Muhammed Ali, temporarily assumed control of Palestine. England and Prussia soon established a strong Protestant presence there.[8] Tensions between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, however, were escalating.[9] Local Muslim populations regarded all Christian foreigners as a singular species and began siphoning their rage onto whatever outlets they perceived as representative of European powers. Though the Islamic world was inching toward a European conception of the nation-state, by and large, it possessed a system of governmental self-understanding that was at odds with the West. It was a system of graduated loyalties, and the Ottoman Sultan was broadly understood to be the Caliph of all Sunni Muslims. It was a holy war, and Europeans, in their eyes, were the perpetrators.[10]

In their disguises, they safely visited the chief of the serpent charmers, Shayk Yusuf ben Makerzi. They learned his secrets and took lessons to become experts in handling live serpents without harm.

They then had the fortune of making the acquaintance of Paulos Metamon, a celebrated Coptic magician, who had many curious books full of charts, diagrams, astrological formulas, and magical incantations, which he delighted in showing to his guests after a proper introduction.

“We are students who have heard of your great learning and skill in magic,” said Blavatsky, “and wish to learn at your feet.”

“I perceive that you are two Franks in disguise, and I have no doubt you are in search of knowledge—of occult and magical lore. I look for coin.”

“I have solved at least one of the mysteries of Egypt,” Blavatsky told Countess Kazenova back at Shepheard’s Hotel. She then released a live serpent loose from a bag she had concealed in the folds of her dress.[11]

SOURCES:

[1] Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo. Lithograph by T. Picken, after a drawing by Machereau, entitled ‘Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo’. French School, ca. 1849. V&A Museum.

[2] Hunter, F. Robert. Egypt Under The Khedives, 1805-1879: From Household Government to Modern Bureaucracy. American University In Cairo Press. Cairo, Egypt (2000): 14-16.

[3] Hunter, F. Robert. Egypt Under the Khedives, 1805-1879: From Household Government to Modern Bureaucracy. American University in Cairo Press. Cairo, Egypt (2000): 14-16; Mestyan, Adam. Arab Patriotism: The Ideology and Culture of Power in Late Ottoman Egypt. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (2017): 115-118.]

[4] Bartlett, William Henry. Forty Days In The Desert On The Track Of The Israelites. Arthur Hall & Co. London, England. (1849): 46.

[5] Bartlett, William Henry. Forty Days In The Desert On The Track Of The Israelites. Arthur Hall & Co. London, England. (1849): Frontispiece.

[6] “Modern Theosophy.” The San Francisco Examiner. (San Francisco, California) September 30, 1886.

[7] Yazbak, Mahmoud. “Templars as Proto-Zionists? The ‘German Colony’ in Late Ottoman Haifa.” Journal of Palestine Studies. Vol. XXVIII, No. 4 (Summer 1999): 40-54.

[8] Kreiger, Barbara. Divine Expectations: An American Woman in 19th-century Palestine. Ohio University Press. Athens, Ohio. (1999): 127.

[9] Badem, Candan. The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856.) Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (2010): 76.

[10] Joffé, E. G. H. “Arab Nationalism and Palestine.” Journal of Peace Research. Vol. XX, No. 2 (June 1983): 157-170.

[11] Rawson, A. L. “Mme. Blavatsky: A Theosophical Occult Apology.” Frank Leslie’s American Magazine. Vol. XXXIII (January-June 1892): 199-208.