1851

For several months after leaving Erivan, Blavatsky lived in the Ottoman Capital of Constantinople, taking up residence in the Hotel d’Angleterre on the Grand Rue de Pera. The hostelry was kept by the hotelier James Missire, the former traveling servant who accompanied A.W. Kinglake, whose travels in the Middle East were immortalized in Eothen (1844.)[1] It was a popular resort for travelers, writers, politicians, and soldiers.[2]

Blavatsky was a daughter of Russia, a land (and people) that vacillated between the West and East. It was a culture in a liminal land primed to reconcile the binaries of her neighbors (yet feared with suspicion on all sides.)[3] On one side there were Westernizers, the liberal reformers of Russia; on the other side were the Russophiles, the traditionalists. In 1847 the Russian Westernizer, Vissarion Belinsky, wrote his famous “Letter to Gogol” in which he described the Orthodox Church as “the bulwark of the whip and the handmaid of despotism,” maintaining that the Russian people were by their very nature, “profoundly atheistic,” and contemptuous of a priesthood that was subject to the government, and upheld its autocracy. Whatever one believed, Russian ecclesiastical policy in the nineteenth century was certainly a factor in the diplomatic mechanizations of Saint Petersburg which endeavored to advance Russian political interests in the Near East. Those who drafted this Near Eastern policy based their project on the enflamed religious consciousness of the Russian people, who, during the course of the previous decades, came to believe in Russia’s messianic mission among the Slavs, the Orthodox Church, and the world. Russian diplomacy fortified itself with religion, and Tsar Nicholas Pavlovich claimed that since the great majority of Christians were Eastern Orthodox, it fell on Russia to provide for their protection.[4]

Ever since the 1820s, Palestine had become a field of particular interest for the European powers. It was, as it had been throughout the ages, a link between commercial routes of East and West, and access to the prized commodities of India, China, and the Far East. While Constantinople was the center of ambassadors, Jerusalem became a central point for European consuls. The activities of these foreign powers intensified when the son of Mehmet Ali of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha, began governing Syria and Palestine. Under his rule, Western religion and education flourished with missionary activity. Schools operating under Protestants and Catholics opened, presses were established, and printed material (especially Bibles) were distributed. To get a foothold in Palestine, European powers would sponsor a local Christian community and “protect” its interests through special provisions extracted from the Sublime Porte. France “adopted” the local Roman Catholics, while Russia “adopted” the Orthodox Church. England (and Prussia,) emerging triumphant from the Napoleonic Wars, were the leading Protestant nations in the region, but with no Christian community in Palestine to “adopt,” they had to be more creative. The British claimed the right to extend their “umbrella of protection” to the Jews and their “restoration” to Palestine. This political hermeneutics could be justified as Anglican cosmology held that the ingathering of the Jews in the Holy Land (and their conversion to Christianity) was a prerequisite for the Second Coming.[5]

In the 1830s Russia gained a privileged status in the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Treaty of Hiinkar Iskelesi (1833,) which terminated the first phase of the complex Turco-Egyptian question. Subsequently, Russian pilgrims (many of them state officials and nobility) began visiting the Holy Land in the 1830s. The greatest promoter of such pilgrimages was A. N. Muraviev, who presented Tsar Nicholas Pavlovich with a copy of his two-volume travelogue. The Tsar, in turn, appointed Muraviev to administer the Holy Synod (a post that Muraviev used to promote interest in Jerusalem.)

The balance shifted in 1841 when diplomatic maneuvering supplanted Russia in favor of Britain and France. The Protestant Bishopric of Jerusalem was subsequently established in 1841 which directed a generous amount of time to proselytizing the Orthodox and Catholics. Levantine Christians, however, tended to view Protestants as “upstarts” without historic claim to the shrines of the Holy Land. It was during this period when a prominent Jewish politician named Mordecai Noah published Discourse On The Restoration Of The Jews at this time. Noah would give lectures on the topic with the intent of raising funds for returning Jews to the Land of Israel. In response to critics who noted that the land was in the Ottoman Empire, Noah suggested that Christians solicit the Sultan for permission for the Jews to legally purchase the land. The decaying Ottoman Empire had paid little attention to malaria-ridden province of Palestine in the past. It was such a low priority in fact that it did not even have the status of an independent colony, rather, it was considered the southern part of the Damascus district.[6] Noah reminded his Christian audience that according to Scripture, the “great events connected with the millennium” would occur only after the restoration of the Jews. The substance of Noah’s talk was not substantially outside the realm of Jewish discourse of the time, but he differed in his call for political sponsorship.[7]

With the weakening of the Russian diplomatic position after 1841, and the encroaching Protestant and Catholic projects in Palestine, the Russians and their Holy Synod “rearranged” their connections with the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and adopted policies similar to their Western rivals. Under the initiative of K. M. Bazili, (the new Russian consul in Beirut,) Count N. A. Protasov (the Over Procurator of the Holy Synod,) and Muraviev, a project was considered that would see to the purchase of buildings in Jerusalem to shelter Russian pilgrims. Muraviev proposed that a nearly abandoned Greek monastery could be converted for such a purpose and supervised by a Russian monk. The ambassador in Constantinople told Bazili that a hostel in a monastery purchased by Russia would antagonize the Greeks who would naturally feel cheated of their income from pilgrims. The Tsar commanded Protasov to give the project over to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and responsibility for the project was transferred from the Synod to diplomats. A collaboration with the Greek Patriarch of Jerusalem was reached, whereby two Greek monasteries were renovated which, in exchange, would serve exclusively as hostels for Russian pilgrims.

Catholic influence in Palestine had been dwindling since the middle of the eighteenth century until 1840. Owing to the numerous pilgrims who came to Jerusalem following the Russo-Turkish wars in the 1820s (and Russia’s increased interest in the Orthodox of the Levant,) Orthodox influence continually increased, even obtaining some Holy Places which formerly belonged to the Catholics. The Catholic Church, consequently, felt the need to increase its activity and regain its position in the region, producing a religious and diplomatic debate directly involving Russia and France. Things came to a head in 1846, when Holy Week overlapped in the Orthodox and Catholic Calendars. The priests of both spiritual bodies each claimed the right to perform the sacrament in the Holy Sepulcher on Good Friday. Old habits die hard, and a brawl ensued resulting in the death of forty people. A year later, on July 23, 1847, Pope Pius IX opened the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem to thwart the influence of Russia as champion of the Orthodox (and England and Germany as protectors of Protestantism.) Count Charles Nesselrode (the Russian Foreign Minister of the 1840s,) meanwhile, had laid the groundwork for the creation of the first Russian Ecclesiastical Mission. Nesselrode, neither a Slav nor Orthodox, was a politician who used the Orthodox Church for purely political objectives. He presented a memorandum to the Holy Synod and the ambassador in Constantinople in which he outlined a more active Orthodox policy, underlining the importance that the Greek Jerusalem Patriarch move his residence from Constantinople to Jerusalem where he could care for his flock. Nesselrode stressed the need for a Russian mission to the Holy Land, but, to avoid antagonizing the Greeks, clarified that it would be subordinated to the church hierarchy in Jerusalem. Nesselrode convinced Tsar Nicholas Pavlovich and the Holy Synod to send a cultured, trustworthy Russian clergyman to Jerusalem to examine the situation and offer moral support to the Greek clergy. Traveling as a humble pilgrim who, this divine would go unobserved, conduct his investigation, and upon his recommendation, future policy for the mission would be drafted.

The clergyman chosen was none other than an old friend of Blavatsky’s mother, Porphyrius Uspensky, whom the government chose primarily because of his knowledge of the Near East. After Odessa, in 1840, he was promoted to the Russian Embassy Church in Vienna. He was recalled in 1842 and sent to Constantinople. Uspensky’s instructions emphasized discretion and winning the support of the Greek clergy. Hot-tempered Uspensky, however, was anything but agreeable. Uspensky’s first reaction to the instructions was demanding more freedom and the insistence that his passport be valid for the entire Ottoman Empire. Soon after arriving in Jerusalem, Uspensky refused to go to the Greek Patriarchate, going instead to where the Russian pilgrims lodged, the monastery of Agion Theodoron. Uspensky complained that the Greek Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher took precautionary measures against him and made an oath not to reveal to him any secrets of the monastery. Uspensky hated the Greek clergy and regarded them as corrupt and not fit for their jobs. During a counter-productive year of inflaming the suspicions among the Greeks, Uspensky returned to Constantinople to await permission from St. Petersburg to visit Egypt. While there, he somehow got involved in the election of the new Jerusalem Patriarch in a manner that embittered the Greeks. The Jerusalem Patriarch who lived in Constantinople under the tutelage of his host, the Ecumenical Patriarch, had the right to nominate his successors. Owing to the influence of the Russian Embassy in Constantinople, it was decided that the election of the Patriarch should take place in Jerusalem, by the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher who made up the church of Jerusalem. This pleased Uspensky, who suspected that losing the right to name a successor, and the subsequent elections would create fissures in the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher, and every election would create more “divisions, machinations and corruption,” and a “house divided against itself shall be destroyed.” The Russian intervention at Constantinople angered the Ecumenical Patriarch, however, for it limited his traditional influence over the Jerusalem Patriarch. Uspensky submitted to V.P. Titov (the Russian ambassador in Constantinople,) two memoranda describing the poor condition of the Jerusalem Church and provided an outline of action that he believed would require Russian intervention to save it. He recommended that a Russian Bishop be sent to Jerusalem accompanied by an educated clergymen. This Bishop would be the center of the Jerusalem Church, and direct both the Synod and the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher. Eventually, a Russian school for the education of native children should be established. He recommended that Russian clergymen study Arabic, and translate Russian books to distribute them to the people of the Holy Land. Additionally, Russia should establish philanthropic centers that would win the confidence of the natives for the Russian clergy. This would be the foundation of the Russian Mission, anchored not in Constantinople or Beirut, but in Jerusalem, and be independent of the future Russian consul with no direct negotiations with the Russian Synod.[8]

Then came the Revolutions. In every nation across Europe (and to some extent the Americas,) the Revolutions of 1848 emerged to challenge the existing order. In Europe, it was the last and greatest of the middle-class revolutions which convulsed periodically since 1789. Galvanized by an optimistic faith in the human capacity for self-government, the revolutions released a torrent of energy that overwhelmed the existing conservative political order. It was the “springtime of nations,” when barricades were erected in the capitals of Europe. Angry mobs vandalized royal palaces; unpopular ministers resigned and went hurrying into exile; and exiled revolutionaries hurried home as heroes. To liberals, it seemed as though a new world was being born, and a new era of liberty, justice, and religious freedom had begun.[9]

1848 was the beginning of the first Italian War of Independence. “Italy” at the time was a collection of kingdoms predominantly under the yolk of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It began when the population of Milan rebelled against their Austrian garrison, and quickly found support among the revolutionaries of the “Young Italy Movement,” like Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, two champions of Italian unification.[10] The author, Ida Hahn-Hahn (a distant relative of Blavatsky,) was an eyewitness to the events in Italy.[11] In her travelogue, Babylon To Jerusalem (1851,) she portrayed the Italian revolutionaries in an unflattering light.[12] The revolutionary spirit swept across the German kingdoms, and it was in this political atmosphere that Karl Marx broke ties with some of Hegel’s major theories, inverting idealism into materialism and questioning the Hegelian conception of State in the Manifesto Of The Communist Party.[13] In the work, co-authored with Friedrich Engels, Marx stated that the foundation of the bourgeois family is capital and private gain.[14] Another result of the Revolution of 1848 was the Basic Rights of the Frankfurt Parliament which declared that civil rights were not conditional on religious belief. This period marked the emancipation of the Jews in many parts of Europe, and an assurance that their religious and cultural autonomy could be expressed under a new system of equality.[15] (The more conservative regions of Europe still prevented Jewish integration.)[16] Jewish emancipation saw new economic mobility, and Jewish migration to predominantly non-Jewish residential areas. Many Jews found their traditional Orthodox religious service to be incongruous with their new social position and cultural identity and joined Reform congregations. The Liberal or Reform movement in Judaism began in Germany at the end of the eighteenth century, and the first Reform temples opened in German cities by the second and third decades of the nineteenth century. (Reform Judaism reached Britain in the 1840s.) The movement, roughly analogous to Protestantism, emphasized the necessity for decorum during services, and prayers in the vernacular. Sermons with a mixed choir and organ replaced the prayers that referred to the coming of the Messiah and the return to Zion with universalistic ones. The reform movement abandoned the idea of a personal Messiah and discarded the national idea for the restorationist ideal of a progressive “Messianic age” in which humanity worshipped the true God and lived in peace and good will.[17] Reform Judaism soon became the dominant expression of Jewish religiosity among prosperous, urban Jews of Germany, Austro-Hungary, Moravia, Bohemia, Britain, and the United States.[18] Not everyone was pleased with this. In the translator’s preface to Babylon To Jerusalem, we find the following statement: “The Jewish element has been so strongly mixed up with German philosophy, the German intellect taken en masse has assumed a half-Jewish, half-heathenish color.”[19]

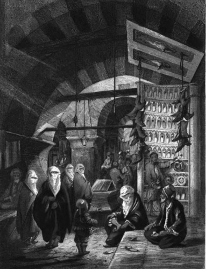

Constantinople Bazaar.[20]

As Germans looked with uncertainty to the future, and their role in it, some looked to the past. It is probably not a coincidence that the folklore-philologist, Jacob Grimm (of Grimm’s Fairy Tales,) addressed German mytho-history in his Geschichte Der Deutschen Sprache (1848.) When discussing the history of the Germans, Grimm states: “Few will be found to question that all the nations of Europe migrated anciently from Asia, their forward march from east to west being prompted by an irresistible impulse whose precise cause is hidden in obscurity.”[21] A year later, in 1849, Max Müller, the father of Religious Studies, entered the conversation.[22] Müller, stating: “We may learn much more of the intellectual state of the primitive and undivided family of the Aryan nations if we use the materials which Comparative Philology has placed at our disposal.”[23] Not long after this, the Count de Gobineau would take the word from philologists, and give it blood quantifiers, claiming the existence of an ancient “Aryan race.”[24]

Blavatsky met many “cast members” of this global drama during her travels. V.P. Titov (the Russian ambassador in Constantinople,) for example, was among those who traveled in the circle that Blavatsky encountered in Büyükdere, a neighborhood in Constantinople. It was in this part of town where Greeks and Armenians lived, and it was in their homes where Italian musicians gave singing, piano, and composition lessons. One such Italian was twenty-nine-year-old Angelo Mariani, of Ravenna. He arrived in Constantinople in to shortly after the Revolution of 1848 to escape Austrian repression, as he had fought as a volunteer in the Sardinian-Piedmontese army. Mariani would develop a new conception of his orchestra-conducting in Constantinople and become one of the key figures in cultivating the international atmosphere of the theatre scene of Pera.[25] Mariani’s mentor was V.P. Titov and had accommodated him in Büyükdere.[26] Mariani was not the only exiled artist revolutionary, as many of Garibaldi’s Redshirts were compelled to seek refuge here when authorities issued arrest warrants against them. Often they lived under assumed names while they continued their professions.[27]

Giovanni Mitrovich.[28]

One day in 1850, while returning home from a promenade in Büyükdere, Blavatsky stumbled over the “apparently dead corpse” of a man. She stood guard over his barely-breathing-corpse while trying in vain to get assistance. A Turkish policeman chanced upon the scene. He asked Blavatsky for “baksheesh” in exchange for help in rolling the supposed corpse into a neighboring ditch. The policeman then showed a decided attraction to my Blavatsky’s rings. He bolted when she aimed her pistol at him. Four hours later, someone finally helped get the stranger off of the ground. He was carried to a nearby Greek hotel, where he was recognized and sufficiently cared for.

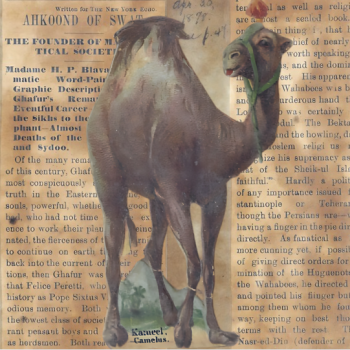

“The Carbonari At Work.”[29]

The following day, the revived “corpse” called on Blavatsky, and introduced himself as “Mitrovitch,” a basso opera singer. He had won acclaim in Verona as Verdi’s titular Attila in 1849 and had now joined Mariani in Constantinople.[30] Despite recovering from an illness, he was performing admirably in Bellini’s La Sonnambula.[31] He explained that he had received three stab wounds in his back from Maltese and Corsican ruffians.[32] He asked Blavatsky to write a letter to his wife, Teresina, and another letter to his mistress (fellow opera singer) Sophie Cruvelli.[33] Blavatsky helped Mitrovitch by writing to Teresina but declined to do so for Cruvelli. Blavatsky learned more about him during this time. He was a Hungarian, the natural son of the Duke of Lucea. His “nom de guerre” was a nod to his birthplace, the town of Mitrovitch. He hated the priests and fought in nearly all the Revolutions of 1848. He was, he explained, a “Good Cousin,” that is, a member of the Italian Carbonari (“Charcoal Burners”) the secret society of revolutionaries which operated a network of cells throughout Europe, Asia, South America, and Russia.

The Carbonari were an offshoot of Freemasonry which emerged in the Kingdom of Naples during the Napoleonic Wars. Their goal was to create a constitutional monarchy or a republic, and “defend the rights of common people against all forms of absolutism.” To achieve this, the Carbonari fomented armed revolts. Giuseppe Mazzini joined the Carbonari in 1827 but was betrayed by a spy, and briefly imprisoned.[34] Mitrovitch further explained that the attack by the Maltese and Corsica ruffians was not a random incident, rather they were hired by Jesuits to kill him. In time Teresina (Mitrovitch’s wife) arrived from Smyrna. The trio became friends, but soon enough the Mitrovitches departed Constantinople, and Blavatsky continued on her travels.[35]

SOURCES:

[1] Smith, Albert. A Month At Constantinople. David Bogue. London, England. (1850): 299.

[2] Çilli, Özgü. “D’Angleterre Oteli Ve Kral Missirie.” Kebikeç. Vol. XLIII. (2017): 369-396.

[3] Riasanovsky, Nicholas Valentine. Russian Identities: A Historical Survey. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2011): 28.

[4] Peretz, Don. The Middle East Today. Bloomsbury Publishing. London, England. (1994): 88.

[5] Yazbak, Mahmoud. “Templars as Proto-Zionists? The ‘German Colony’ in Late Ottoman Haifa.” Journal of Palestine Studies. Vol. XXVIII, No. 4 (Summer 1999): 40-54.

[6] Tal, Alon. “Enduring Technological Optimism: Zionism’s Environmental Ethic and Its Influence on Israel’s Environmental History.” Environmental History. Vol. XIII, No. 2 (April 2008): 275-305.

[7] Kreiger, Barbara. Divine Expectations: An American Woman in 19th-century Palestine. Ohio University Press. Athens, Ohio. (1999): 1-7.

[8] Stavrou, Theofanis George. “Russian Interest In The Levant 1843-1848: Porfirii Uspenskii And Establishment Of The First Russian Ecclesiastical Mission In Jerusalem.” Middle East Journal. Vol. XVII, No. 1/2 (1963): 91–103.

[9] Hamerow, Theodore S. “History and the German Revolution of 1848.” The American Historical Review. Vol. LX, No. 1 (October 1954): 27–44.

[10] Daniel, Frederick S. “The Unifying Of Italy.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XXXVII, No. 1 (January 1894): 37-47.

[11] “About Spiritualism: An Interview With Madame Blavatsky.” The Daily Graphic. (New York, New York) November 13, 1874.

[12] “I spent the winter of that year of shame 1848 in the revolutionized cities of Palermo and Naples. The revolutionists had prepared their work there as elsewhere; that is, they had exclaimed and protested so furiously against all that stood in their way, and everything that was opposed to their views—they invented and published such falsehoods calumnies, and nonsense, that the bewildered crowd at last believed them; they directed all their plans against the one hated point—and there, as everywhere else, the authorities were frightened.” [Hahn-Hahn, Ida. From Babylon To Jerusalem. T.C. Newby. London, England. (1851): 103.]

[13] Gilman, Sander L. “Karl Marx and the Secret Language of Jews.” Modern Judaism. Vol. IV, No. 3 (October 1984): 275-294.

[14] It further stated: “In its completely developed form this family exists only among the bourgeoisie. But this state of things finds its complement in the practical absence of the family among the proletarians, and in public prostitution. The bourgeois family will vanish as a matter of course when its complement vanishes, and both will vanish with the vanishing of capital. Do you charge us with wanting to stop the exploitation of children by their parents? To this crime we plead guilty […] The bourgeois clap-trap about the family and education, about the hallowed co-relation of parent and child, become all the more disgusting, the more, by the action of Modern Industry, all family ties among the proletarians are torn asunder, and their children transformed into simple articles of commerce and instruments of labour.”

Marx, Karl; Engels Friedrich. Manifesto of the Communist Party. Charles H. Kerr & Company. Chicago, Illinois. (1906): 40-41

[15] Baron, Salo W. “The Impact of the Revolution of 1848 on Jewish Emancipation.” Jewish Social Studies. Vol. XI, No. 3 (July 1949): 195-248.

[16] Adler, Cyrus. “Oscar S. Straus: A Biographical Sketch.” The American Jewish Yearbook. Vol. XXIX. (1928): 145-155; Harris, James F. “Rethinking the Categories of the German Revolution of 1848: The Emergence of Popular Conservatism in Bavaria.” Central European History. Vol. XXV, No. 2 (1992): 123–148.

[17] Levy, Clifton Harry. “Jewish Colonies In Palestine.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. XLI, No. 213 (November 13, 1897): 1130.

[18] Sharot, Stephen. “Reform and Liberal Judaism in London: 1840-1940.” Jewish Social Studies. Vol. LXI, No. 3/4 (Summer-Autumn 1879): 211-228.

[19] “It has been asserted by many, and with great truth, the Revolution of 1848 was a literary revolution. This much is certain, the whole German literature, since the days of Lessing, has been essentially anti-Christian […] The Reformation destroyed the Christian character of German literature; and at a subsequent period, German princes aided and encouraged the spirit of infidelity, under the false name of enlightenment and freedom of thought […] It was not a Protestant literature as in England; no, if any one supposes the positive doctrines of Protestantism to be contained in the modern German literature, he is much mistaken. It contains all the different shades of a removal from Christianity—rationalism, deism, pantheism, atheism, and adoration of self, the creature instead of the Creator runs through all. And as the Jewish element has been so strongly mixed up with German philosophy, the German intellect taken en masse has assumed a half-Jewish, half-heathenish color. Of late years literature and art have been sold to the Jews (with a few noble exceptions,) and they are turning them, in combination with various other means, to their own advantage.” [Hahn-Hahn, Ida. From Babylon To Jerusalem. T.C. Newby. London, England. (1851): ix-x.]

[20] Smith, Albert. A Month At Constantinople. David Bogue. London, England. (1850): Frontispiece.

[21] Grimm, Jacob. Geschichte Der Deutschen Sprache. Verlag Von S. Hirzel. Leipzig, Germany. (1880): 6.

[22] Johnston, Charles. “An Estimate Of Max Müller: 1823-1900.” The American Monthly Review Of Reviews. Vol. XXII., No. 6. (December 1900): 703-706.

[23] Müller, Friedrich Max. Essays On Mythology, Traditions, and Customs. Longmans, Green, and Company. London, England. (1867): 20-21.

[24] Dunlap, Knight. “The Great Aryan Myth.” The Scientific Monthly. Vol. LIX, No. 4 (October 1944): 296-300.

[25] Cattelan, Vittorio. “The Italian Opera Culture In Constantinople During The Nineteenth Century. New Data and Some Ideological Issues.” Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie Orientale. Vol. LIV. Supplemento. (2018): 621-656.

[26] Stavrou, Theofanis George. “Russian Interest In The Levant 1843-1848: Porfirii Uspenskii And Establishment Of The First Russian Ecclesiastical Mission In Jerusalem.” Middle East Journal. Vol. XVII, No. 1/2 (1963): 91–103.

[27] Nagy, László Bálint. “Helena Blavatsky’s Lover And The ‘Redshirt’ Rossi Garibaldi’s Immigrant Soldier Artists In Hungary And Transylvania.” [https://www.academia.edu/44005223/The_lover_of_Helena_Petrovna_Blavatsky_and_the_Redshirt_Rossi_Two_immigrant_soldier_artists_of_Giuseppe_Garibaldi_in_Hungary_and_Transylvania.]

[28] Nagy, László Bálint. “Helena Blavatsky’s Lover And The ‘Redshirt’ Rossi Garibaldi’s Immigrant Soldier Artists In Hungary And Transylvania.” [https://www.academia.edu/44005223/The_lover_of_Helena_Petrovna_Blavatsky_and_the_Redshirt_Rossi_Two_immigrant_soldier_artists_of_Giuseppe_Garibaldi_in_Hungary_and_Transylvania.]

[29] Taxil, Leo. Les Mystères De La Franc-Maçonnerie. Letouzey & Ané. Paris, France. (1887): 433.

[30] “The deep bass Mitrouvich [recte Mitrovich ] fits the role of the protagonist perfectly. Endowed with a beautiful and vigorous voice, this is a singer who has a lot of intelligence, but who, still fresh from illness, was unable last night to show off his beautiful talents.” [Giovanni Ricordi to Carlo Predrotti. Verona, Italy. December 12, 1849. (LLET012496.) Archivio Storico Ricordi. Collezione Digitale.]

[31] “On the evening of the 14th of this month the Sonnabula [sic] was staged. This divine music was excellently interpreted by the leading lady Mrs. Penco, the tenor Bozzetti and the bass Mitrovich. Penco in her opening cavatina made us remember the good times of the excellent Italian singing school which has now unfortunately fallen into decline. Thus the Tenor Bozzetti, who in Lucia left something to be desired in terms of strength, is vividly in his place in this opera. Mitrovich played his small part well and received much applause for his comeback.” [Angelo Mariani to Giovanni Ricordi. Constantinople, Turkey. December 21, 1850. (LLET010308.) Archivio Storico Ricordi. Collezione Digitale.]

[32] Mariani mentions that “Mitrovich recovered from a mild illness” at this time. [Angelo Mariani to Giovanni Ricordi. Constantinople, Turkey. April 12, 1851. (LLET010312.) Archivio Storico Ricordi. Collezione Digitale.]

[33] Cranston, Sylvia. HPB: The Extraordinary Life And Influence Of Helena Blavatsky. Path Publishing House. Santa Barbara, California. (1993): 77.

[34] Maurice, Charles Edmund. The Revolutionary Movement of 1848-9 In Italy, Austria-Hungary, And Germany. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1887): 57.

[35] Sinnett, Alfred Percy. The Letters Of H. P. Blavatsky To A. P. Sinnett And Other Miscellaneous Letters. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. London, England. (1925): 143-144.