When President Jimmy Carter died on December 29th, 2024, almost every obituary on the 39th president made some mention of his deep Christian faith. A New York Times article featuring seventeen objects that exemplify Carter’s extraordinary life included a wooden cross hanging in Maranatha Baptist Church, which Carter made himself. Carter’s identity as a born-again Christian was certainly no secret, either during his presidency or after, and it helped to shape his politics in a way that was distinctly different from the Religious Right, which arguably rose to oppose him specifically, at least if one associates the Religious Right with the 1979 founding of the Moral Majority group. Carter was eulogized by religious historian Randall Balmer in Politico as the last of his kind: a progressive evangelical. Balmer defined progressive evangelicals as a group who have taken Jesus’s commands to be peacemakers and care for those on the margins of society, or the “least of these,” as Jesus says in Matthew 25, seriously. Balmer went on to compare Carter’s rhetoric in a famous speech he gave as governor of Georgia to the Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern, perhaps the most famous document of Cold War-era progressive evangelicalism. Carter’s center-left politics and his eventual departure from the Southern Baptist Convention following the Conservative Resurgence (or takeover) might lead one to logically group Carter with other progressive evangelicals. Balmer did, as did Jim Wallis, the founder of Sojourners magazine and in many ways the face of progressive evangelicalism. Carter’s identification with progressive evangelicals may be appropriate for Carter’s post-presidency, but during his presidency, the relationship was much more complicated. In fact, in the research that I did for my master’s thesis on Carter’s relationship with white evangelicals in Texas, some of the harshest criticism did not come from conservatives. Instead, it came from evangelical progressives in the pages of Sojourners.

A Red-Hot Magazine and a Lukewarm Candidate

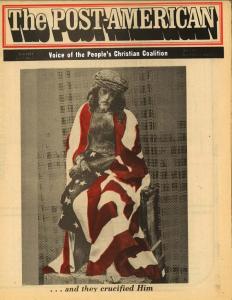

Sojourners magazine was founded in the fall of 1971, but with a different title that hints at the magazine’s more radical origins: the Post American. The magazine was conceived of as a messaging arm of Sojourners Community, an intentional Christian community originally founded by seminary students at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Rogers Park, Illinois. The group eventually decamped for Washington, D.C., where they continued their intentional Christian community and continued to publish what was now named Sojourners. They were heavily influenced by interpretations of scripture that actively called them to advocate for the poor, the marginalized, and to wage peace in the world. As a result, the Vietnam War proved to be a radicalizing event for many of them, including Jim Wallis, who briefly joined the Students for a Democratic Society before entering seminary. They viewed the war as an atrocity the nation must immediately end and repent of, meaning they were no fans of most of the American state. With the rare exception of politicians like George McGovern and Mark Hatfield (a rare progressive evangelical Republican who became friendly with Wallis and Sojourners), no one was outright condemning the war in the two major political parties, nor were American evangelicals as a whole for that matter. A small cadre of them did form an Evangelicals for McGovern group in 1972 when the senator from South Dakota won the Democratic nomination on an explicitly anti-war platform, but his campaign was doomed to be a 49-state blowout to Richard Nixon, who was embraced by the vast majority of American evangelicals. However, within less than two years, he infamously resigned in disgrace, which brought America to Jimmy Carter, the one-term governor of Georgia. It can be easy to forget, but Carter was more conservative than one might initially expect. In an unsightly moment of politicking, his 1970 campaign for governor employed racial dog-whistling, and he was also in favor of the death penalty and the Hyde Amendment that barred federal funds from being spent on abortions. Additionally, his calls for reform in the 1976 campaign were rather vague, with promises that he as the president “would never lie to [America],” and that the nation “deserved a government as good as its people.” To many of the authors at Sojourners, Carter’s rhetoric was mere empty calories, meant to make Americans feel good in the bicentennial, with little to offer in real change.

In October of 1976, the final month before the election, Sojourners’ cover story was entitled “Election ’76: The Seduction of the Church,” likely riffing on the Newsweek cover story from the same month that declared 1976 “the year of the evangelical.” In that October edition of Sojourners, William Stringfellow, the famous theologian and civil rights activist, wrote “An Open Letter to Jimmy Carter,” which excoriated the self-professed born-again candidate for president. To Stringfellow, Carter was the political embodiment of middle-of-the-road compromise and the lukewarmness Christ condemns in the church of Laodicea in the book of Revelation. Stringfellow saw a serious moral and political crisis in the American government that began with the rise of the military-industrial complex following World War II and was made clear in the horrors and butchery of the Vietnam War. While Carter made reference to Vietnam and the intelligence community in his campaign, most notably promising to pardon draft evaders (although he was quick to state that such a pardon didn’t mean he thought such evaders were morally right), he did not campaign on serious attempts to reform or limit the power of the intelligence community or defense apparatus that approved of the Vietnam War and other Cold War activities. In other words, to progressive evangelicals at Sojourners, Carter did not go far enough. He was still operating as a typical American politician when he needed to become a post-American to truly live out his Christian faith. In fact, providing half-measures of change but not wholesale reform might be even more dangerous than the status quo. As Stringfellow wrote, “to hear the trivial doctrine that the need is to elect trustworthy persons to succeed the wicked in high places becomes a very melancholy experience, aggravating, if anything, the nation’s plight.” The theologian closed his article by suggesting that abstaining from voting for Carter or Ford in the election may be an act of spiritual and political maturity and witness.

That attitude permeated Sojourners throughout Carter’s one term. While they certainly condemned and distanced themselves from the Moral Majority and the Religious Right, they also criticized Carter heavily. The magazine ran an article in the weeks prior to the 1980 election that compared the contest between Carter and the arch-conservative Reagan to a baseball game, sending the message that in the mind of the author, the election had little consequence.

Progressive evangelicals’ attitudes towards Carter notably changed after he left office. This was in no small part due to Carter’s humanitarian efforts both at home and abroad, which included work for Habitat for Humanity, attempts through the Carter Center to end Guinea Worm and River Blindness, and nonpartisan election watching. Additionally, in 2000, Carter left the SBC over their rigid doctrine on women’s roles in the church, a departure which warmed progressive evangelicals’ relationship to him. However, progressive evangelicals’ post-presidential change in posture toward Carter should not be retroactively extended to include his candidacy and presidency. While some left-leaning evangelicals supported him, the progressive evangelical movement did not universally love him. Carter was many things, but he was not “the last of the progressive evangelicals,” at least if the writers at Sojourners had anything to say about it.

David Nanninga is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of History at Baylor University. His research focuses on American conservatism and neoliberalism in the late 20th century and their relationship to politics, sports, and Christianity.

David Nanninga is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of History at Baylor University. His research focuses on American conservatism and neoliberalism in the late 20th century and their relationship to politics, sports, and Christianity.