This past summer I began a series of posts reviewing David Bentley Hart’s book Tradition and Apocalypse. In the first post I discussed the general theological and historical issues Hart is addressing. In particular, I gave my own account of the development of early Christian tradition, particularly the doctrine of the Trinity, which is Hart’s major “test case.” In the second post, I discussed how the Reformation (my own area of expertise) fits into the picture, and the different ways in which Protestants and Catholics attempted to create a coherent concept of tradition and the continuity of the faith in the face of the disruptions of the sixteenth century. And in the third, I discussed Hart’s critique of Newman. But I never got around to discussing Hart’s core argument. So here I am to finish the series.

Looking in the rear view mirror

Hart argues that the only real continuity we can find in the Christian tradition is one that looks backward, not forward. When critiquing Newman, he made the point that Newman’s signs of “true development” could in principle be applied to pretty much any tradition that managed to survive over time. We look back and see in the past the seeds of current developments. We can construct a “type” which has been preserved over time, because we define the “type” by what exists in our own day. The very changes that appear to present a problem for tradition can be seen as evidence of the dynamism of tradition. When the tradition has to borrow from other traditions, this is proof of its “assimilative” power, and so on.

Hart is, I think, closer to Newman than he wants to admit. He has found a way in which all of these moves can be legitimate. Simply admit, honestly, that all of these signs of continuity are only seen in the rear view mirror. They aren’t ways in which we can predict what is going to come in the future. But we can look back at the past and see how everything has led to the point where we are now. Some things that might have seemed important in the past have been discarded. Others that our ancestors would never have thought of, or might even have rejected with horror, are now treasured aspects of the tradition. The story is ever-changing as we incorporate more and more new developments. We constantly retell the story in such a way that it makes sense of everything that has gone before.

Just another form of liberal theology?

How does this position differ substantially from that of liberal Christian theology? Hart doesn’t really address this, and it’s probably not a worry for him. It used to be a worry for me. I thought I had to maintain some fairly robust understanding of continuity or else I would become a “liberal” and have no substantive, meaningful faith at all. More seriously, conservative Christians raise the specter of a liberal faith that simply imitates whatever happens to be fashionable at a given time and place. Given the extent to which “conservative” Christianity frequently sells out to the more authoritarian impulses of a particular time and place, I find this worry, too, much less cogent than I used to. But I still think that it’s important for Christianity to be a counter-cultural, subversive force, and not something that just tells us in nice words what we already knew.

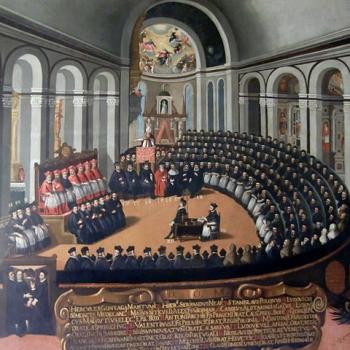

This is why the term “apocalypse” highlighted in Hart’s title is vitally important. Authentic tradition, in Hart’s account, always has a radical, surprising character to it. Again, the doctrine of the Trinity is the prime example. It’s not simply a reaffirmation of what was always believed. Arianism fit much better with existing cultural assumptions about the nature of the divine, as well as, in many ways, with previous tradition. (As I’ve said in an earlier post, I think Hart may overstate that last point a bit.) But the Trinity, in retrospect, deepened and transformed what Christians believed about God and about the significance of the life and work of Jesus.

A helpful parallel in philosophy of science may be the distinction Imre Lakatos made between “progressive research programs” and “degenerative research programs.” A good scientific theory, according to Lakatos, is one that keeps making new predictions and giving rise to new discoveries. A degenerative one keeps having to explain away objections to its existing claims, without actually giving rise to any new insights.

It seems to me that both “conservative” and “liberal” theologies can be, in Lakatos’ terms, “degenerative.” Conservatism degenerates when it’s constantly fighting a rear-guard action against new, threatening ideas. Liberalism degenerates when it becomes simply a way of “saving” Christianity by accommodating it to new trends, without having anything transformative to say to secular culture. Against both of these, Hart offers an approach that is “liberal” in its openness to future change while celebrating the glorious oddness of historic Christianity.

I think this is fundamentally the right approach and offers us a way out of the sterile “liberal/conservative” dichotomy. But it can only do that if we have the courage to be willing to appear unfashionably “conservative” in some contexts and scarily “liberal” in others. And perhaps even more, we need the courage to accept that we are going to be wrong much of the time. There is no inherent logic that will enable us to deduce the right theological answer to new questions. We have to be willing to take the risk of being recorded in the history of the tradition as heretics who pursued dead ends, or, alternatively, as blind conservatives who clung to ideas which others of our time had wisely discarded. We have to let the adventure of the Tradition proceed, not knowing how it will end.

Apocalyptic Papalism?

Now I’m Catholic and this is an explicitly Catholic blog. Catholic readers are probably impatiently wondering, at this point, “But what about the Church?” And one of the striking features of Tradition and Apocalypse is that Hart doesn’t really have much to say about the Church. This is one of the things that bothers many people about his more recent work. To some extent it’s a Catholic/Orthodox difference. Catholics are much more willing than the Orthodox to appeal to the Church as a sort of external guarantor of orthodoxy, apart from arguments about the intrinsic compatibility of a given idea with what has come before.

For the Orthodox, as I understand their position, the only way to tell for sure that one bishop is orthodox and another not is to judge their relative fidelity to the Tradition. Catholics, of course, argue that the bishops who remain in communion with Rome are the ones to be followed, and that Rome is preserved by God from falling into dogmatic error. Hart obviously does not hold this view. At the same time, his dynamic understanding of orthodoxy is much more compatible with post-Vatican-II Catholicism (and, in spite of his disclaimers, even with Newman) than with the rejection of development that one typically hears from the Orthodox.

But it’s none of my business to evaluate Hart’s position from an Orthodox perspective. From a Catholic perspective, the question is whether his position is compatible with our belief in the infallibility of the Church, and indeed specifically of the Pope. And if it is, would a “Hartian” Catholicism really just look like the “add Pope and stir” approach that many accuse post-Vatican-II Catholicism of? I.e., would we be left with simply following blindly whatever the Pope said, confident that this was pointing us toward the “apocalyptic” goal of the Tradition?

I certainly think that many of the worries Catholics have about Pope Francis would go away if Catholics in general adopted Hart’s approach. If the true meaning of the Tradition is only available in hindsight, then, given our beliefs in the nature of the Papacy, it makes sense to trust the Pope. And I generally do trust this Pope in particular, though I disagree with some of the things he does. But I’m very uncomfortable (as I’m sure Hart is too, being Orthodox and all) with just blindly trusting the Pope to be the Voice of the Apocalypse.

Rather, I believe that the role of the Papacy is to keep us all together while the Spirit leads us toward our apocalyptic goal. It’s not that the Pope is always right, but that we can trust that the Spirit will never allow him to be so wrong that we have to leave the community that is in union with him.

Tradition and Community

So while I think Hart offers a helpful challenge to how we Catholics tend to think about the Tradition, I think our understanding of the Church also has something to offer that is missing in his account. Traditions are inherently tied to communities.

The fundamental problem with the Christian obsession with orthodoxy has been, historically, that it leads to breaking the bonds of charity that hold us together. I’m including in that both obviously evil acts such as burning heretics at the stake and the nonviolent act of “starting a new church” which has become a matter of course for most modern Protestants. (The recent split in the UMC brought this home to me and played a role in finally pushing me over the edge into Catholicism, aback in 2016-17 when I realized that the split was probably inevitable and Methodist friends I respected highly argued for it as a good thing.)

Hart’s understanding of tradition certainly points up the wickedness and folly of the ways we have treated alleged “heretics” in the past. But it also, I think, implies that striking off with a small group of like-minded people in the search of some more authentic version of the tradition is a highly unwise approach.

If we’re all moving toward an apocalyptic goal whose precise nature we cannot predict, we need to do it together.

Photo of the Camino de Santiago by Les routes sans fin(s) on Unsplash