Whenever we think of historic accounts of witchcraft, there are a number of cases that are frequently mentioned. In particular, these are the ones that popular authors have included in their studies, from Margaret Murray to Emma Wilby. But there is one incident in history that incorporates all of the tropes and stereotypes of witchcraft and magic in the early modern period, including the black mass, black magic, clergy, love spells, witchcraft, devilish pacts, poisoning, abortions, and child sacrifice. What’s more, the incident attests to a conspiracy that went the heart of French royalty and threatened the king’s court, resulting in the execution of 34 people. The Affair of the Poisons was a strange and especially Parisian incident in which an alleged circle of sorcerers and poisoners was uncovered, composed of a variety of magical practitioners, gentry, commoner and devilish clerics all centred around a renowned and prosperous fortune-teller called La Voisin.

What prompted the Affair of the Poisons in 1677 came about due to a perceived threat to king Louis XIV (who styled himself the Sun King) and a general fear of poisoning that had made its way into his court. In 1676, the Brinvilliers murder case came to its grisly conclusion with the execution of the the Marquis de Brinvilliers, a member of the nobility and daughter of the Civil Lieutenant of the City of Paris — one of the two most important magisterial roles in Paris. Brinvilliers had poisoned her father, and her two brothers, ostensibly for pecuniary motives, together with her lover Captain Godin de Sainte-Croix, a rather rakish fellow of apparent good looks and charm, and friend of the Marquis’ husband. While Brinvilliers’ husband may not have been so offended by his wife’s dalliance with his friend, her father was less inclined and made out an order in the King’s name for Sainte-Croix’s arrest. The Marquis de Brinvilliers later said of the murder of her father that “One should never annoy anybody; if Sainte-Croix had not been put in the Bastille perhaps nothing would have happened.”[1]

After six weeks imprisonment, Sainte-Croix was released and continued the affair, renting a property in Place Maubert where he pursued the study of alchemy. However, there is more than a suggestion that his experiments were more concerned with counterfeiting coins, or else the fabrication of poisons. [2] Before her execution, Brinvilliers implicated the Swiss ‘apothecary in ordinary’ to King Louis XIV, Christophe Glaser, in supplying the poison used in the murder of her father and brothers. Indeed, Glaser did write about the preparation of vitriol, arsenic and corrosive sublimate in his 1663 book The Compleat Chymist. Be that as it may, the poisons were readily available and well-known at the time, and the attachment of Glaser’s name is likely nothing more than a coincidence. For instance, in one of the letters from Brinvilliers to Sainte-Croix, the murderess implies that she might have killed herself using “Glaser’s recipe, which you gave me at such a high price.” [3]

In the lead up to the Affair of the Poisons, the Brinvilliers case sparked a panic amongst the nobility that they might be susceptible to poisoning. Indeed, the fervour reached king Louis XIV himself, prompting the arrest of two Parisian fortune tellers who were suspected of supplying their wealthy clients with poisons. The panic grew rapidly and soon the king ordered a commission to investigate the threat and implication of a plot to poison him, leading to multiple arrests amongst the city’s underworld, especially those who “made a living by predicting the future, advising on love affairs or offering to use their magic powers by providing contact with the spirit world.” [4]

Apparently not desirous of the ordinary courts to become overwhelmed with poisoning cases, the king ordered a commission to investigate and prosecute cases of poisoning, especially as it pertained to the nobility and, potentially, himself. While the king’s wishes to unburden the courts sounds admirable, it should be noted that he also required this to be undertaken with discretion and secrecy lest ‘high-ranking’ individuals become implicated. [5] It wasn’t long before several fortune tellers were taken and quizzed regarding their knowledge and use of esoteric arts, including poisoning. At this juncture, it behoves the author to remind the fair reader of the close association, historically, between poison and witchcraft…

Historically, witchcraft has been very closely associated — at times synonymous with — poisoning. The Roman term for a sorceress who employed drugs, potions and poisons, venefica refers especially to a female witch adept in the preparation of herbs and other material for various, and nefarious, reasons. Such use of botanics has historically been sometimes regarded a somewhat feminine pursuit, but not always, with the gathering and application of plant material to heal or harm being a particular and, at times, elusive art. Whilst many made use of the early herbalists in the absence of medicine, doctors and physicians, their knowledge could also hold them in suspicion when things went wrong. For instance, the famous herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616 – 1654) operated as an apothecary and astrologer, working out of his pharmacy in Spitalfields, and his 1652 Culpeper’s Herbal is still highly acclaimed and used today. This, however, did not make him immune to accusations of witchcraft when, in 1643, he was indicted for bewitching the Shoreditch widow Sarah Lynge. Whilst the details are lost to history, and we can say with certainty that he was acquitted, we can only speculate that Lynge, or somebody close to her, had been a client of Culpeper’s who was dissatisfied with his services. Needless to say, the proximity of herbalism, chemistry, and pharmacy with astrology and occult practices was such that they could commonly be regarded as hand in glove with witchcraft.

Returning to the Affair of the Poisons, it was not long before the arrested fortune tellers circulated a name that the commission had not yet heard. Principal amongst the first arrestees was Marie Bosse, arrested in January 1679 after she was found to have boasted at a dinner party that she made her money supplying poison — a dangerous admission that resulted in her being burnt in May 1679, a mere five months after her arrest. Depositions of Marie Bosse made frequent mention of a network of poisoners and occultists headed by the mysterious La Voisin, a fellow diviniress who performed occasional abortions, practiced black magic and provided poisons, powders and philtres through her circle of nefarious magicians, diviners and priests.

La Voisin had apparently developed her fortune telling ability from the age of nine and, after her husband’s jewellery business had gone bankrupt, she supported her family at their home in Rue Beauregard, outside the Paris city walls, where she would meet clients in a garden pavilion. Whilst it appeared that La Voisin made a significant living for herself and her family through her midwifery and dinivations — and alleged sorcery and poisoning — she was evidently an alcoholic and her marriage appeared unhappy, resulting in her pursing an active sex life outside of the marital bed. This involved multiple lovers, including magicians, alchemists, aristocracy and a tavern keeper. [6] La Voison’s drinking often loosened her lips, causing her to speak more than perhaps she should about her activities, betraying her outwardly pious, churchgoing appearance.

La Voisin was first questioned on the 17th March 1679, during which she denied any wrong-doing and attempted to weave a narrative that implicated Marie Bosse. The following day, 18th March, La Bosse and La Voisin were brought together, wherein the former threw a slew of accusations against the latter, besmirching her name and character, as well as that of her associations. One particular point of note came when Bosse accused Voisin of wanting her husband dead, and that her lover, the magician Lesage, had buried a sheep’s heart in her garden to affect such. Whilst denying the bulk of accusations, this one she admitted had troubled her and Voisin confessed that she had been troubled following this incident as her husband was inflicted with a stomach ache, causing her to seek absolution from the priest and having Lesage undo the spell. Furthermore, La Voisin damningly admitted an occasion when ladies of high rank had sought her assistance in procuring poison. What eventually unravelled over the course of the days, weeks and months that followed was a series of deaths and, by implication poisonings, by high ranking women facilitated by a cohort of dark individuals who dabbled in dirty deeds. So many names were eventually teased out that the English ambassador to France reported: “The multitude of distinguished people arrested for poisoning grows every day.” [7] Aside from the poisoning, another aspect of La Voisin and her associate’s activities included abortions, “saving ladies of rank from embarrassing pregnancies.” [8]

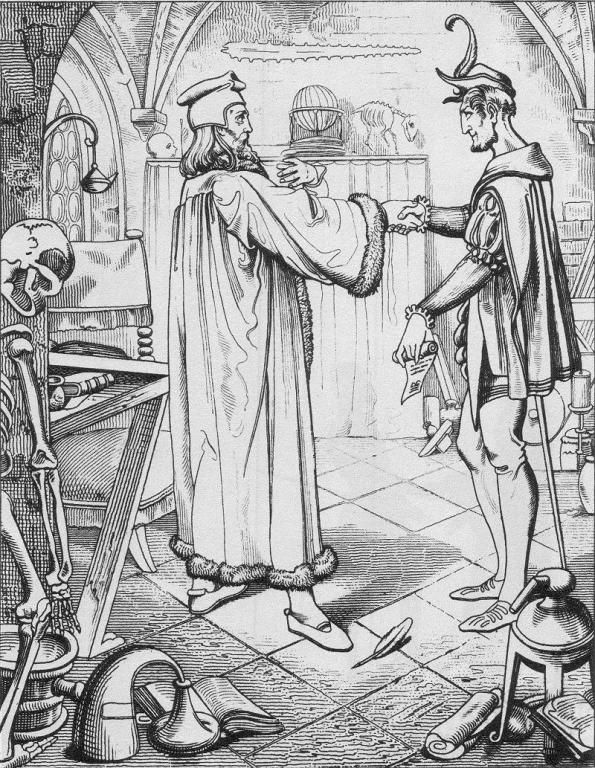

By September, La Voisin had fully implicated a number of clients and associates, and was now incriminating further the magician Adam du Coeuret, who called himself Lesage (“the wise one”). In his fifties, Lesage did not allow Voisin’s husband to be an obstacle to becoming her lover. In 1667, she says, La Voisin introduced Lesage to the twenty-seven year old priest Francois Mariette. Together, the trio performed folk magics and sorceries on behalf of a clientele that made them prosperous. In 1668, Lesage and Mariette were arrested and tried for committing impieties. Whilst Lesage was accused of saying prayers over the corpses of flayed frogs, reminiscent of the Toad-Bone Rite perhaps, Mariette more damningly admitted to seeing clients privately in order to say gospels over them while they knelt. Furthermore, it is possible that he possessed and used grimoires, including the Enchiridion, which was an exhibit during the later trial of Lesage. In terms of the Affair of the Poisons, the most incriminating evidence of this 1668 episode that would be important ten years later was that the priest Mariette confessed that one of his clients had been the Marquis de Montespan who was to become the most celebrated mistress of king Louis XIV by 1679 and the link that brings the sordid Affair of the Poisons to the bedchamber of the Sun King.

In his own testimony following his inevitable arrest during the Affair of the Poisons, Lesage implicated a number of Parisian priests as being involved in diabolic sorcery. As shocking as this might first appear, it should be remembered that many grimoires and much magical literature was written, recorded, preserved and used by clergy and incorporates the rite of exorcism, for example. Consider Johannes Trithemeus (1462 – 1516), who was an inflential occultist whose students included Paracelsus and Agrippa, and whose Steganographia was a favourite of John Dee.

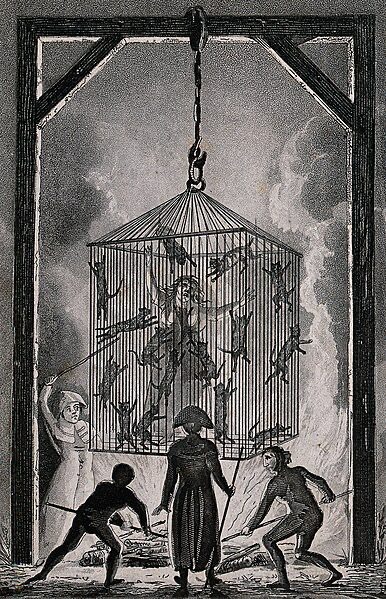

By Autumn of 1679, the commission had expanded its net and a swathe of diviners, sorceresses and magicians were being questioned. In 1680, one implicated by Lesage, Francoise Filastre, in May introduced ideas of devilish pacts that high ranking women in the court had engaged in and asked, panicked about discovery, to be recovered. Filastre confessed to trying to position herself in the service of the king’s mistress, Mlle de Fontages, whilst she also said that she attended a black magic ceremony, seven years prior, during which she gave birth to her lover’s child. In addition, she had been present at multiple black masses over the years, all officiate as is custom by priests. Filastre named a priest who presided over one such black mass whereby ‘three demon princes’ were conjured to enact a pact with the devil in order to procure more occult power and, unbelievably, when the priest Jacques Cotton was arrested and quizzed on this, he freely admitted to it! [9] Furthermore, Cotton owned up to a host of ceremonies for various purposes, from using wax figures and saying mass over powders that were passed on to the circle of poisoners and sorcerers to be sold to clientele.

One priest that Filastre named was Abbé Étienne Guibourg, who subsequently claimed that, ten years previously, he had performed child sacrifice and saying the black mass over the nude body of Madame de Montespan, in order to make her the favoured mistress of the Sun King Louis XIV. Guibourg was, in 1680, seventy years old and had resoundingly violated his vows by keeping a concubine. The damning testimony of the elderly clergyman began immediately upon his questioning and he promptly admitted that he had celebrated the mass over the afterbirth of Filastre’s child born during such a ceremony. Following this claim, Guibourg was asked about saying the mass upon the stomach of naked women, to which he confessed with details of his first and subsequent performances of the rite. The Affair of the Poisons had now moved from poisoning to devil worship and black mass amongst the underbelly of Paris, through its clergy and the elite.

As is the case with many such trials — such as that of the Pendle Witches — the most devastating deposition comes from the daughter of one of the main women accused, Marie Monvoisin. In her testimony, Marie alleged that, whenever she feared the king’s love waning, Madam de Montespan would attend La Voisin’s residence where the sorceress who would arrange for a black mass to be said in order to regain the monarch’s favour, in addition to the provision of love powders to be administered to theSun King. Furthermore, Marie placed Guibourg at the Voisin family home, reciting the black mass over the altar of a naked woman who, on occasion, was Montespan herself on at least three separate instances.

Filastre was sentenced to torture and then death, with the misguided hope that being so pressed would release more valuable information. Of course, it provided the commissioners with precisely the knowledge that Filastre thought that they wanted to hear in order to make the torture end and, prior to her execution, the convicted witch unburdened herself by admitting that all of her testimony had been false. She did own that she had procured poisons, but suggested that this had been intended for the wife of her lover. By this time, however, the cat was out of the bag and the whole Affair was ablaze.

In all, the Affair of the Poisons saw 319 arrest warrants, of which 194 people were retained in custody. 104 individuals were tried by the commission, of which 36 death sentences were passed which resulted in 34 executions with 2 people dying during torture. 16 individuals received absolute discharge, while 17 offenders were banished from the realm. An unknown number received sundry charges, such as fines. Due to the proximity to the king and his favourite courtesan, who had borne several of his children, those associated with Montespan were deemed too dangerous and, therefore, imprisoned for the rest of their lives without the embarrassment of ever seeing trial, their testimony sealed to prevent the whole incident ever getting a public airing. These individuals included La Voisin’s daughter, Marie Monvoisin, the magician Lesage, and the priest Guibourg. Worse still, there were those who were innocent but had been arrested and learnt too much — by being held in a cell with Guibourg, for example. Some of these were placed in convents to secure their silence, others were escorted outside of France with a travel allowance and an annual payment to ensure their quiet on the matter. Many other astrologers, apothecaries, alchemists, diviners, herbalists and diverse other common individuals were disappeared forever and forgotten in the confines of the prison system after being rounded up in the maelstrom.

Remarkably, despite being kept personally abreast of all that occurred during the commission, the king never turned on Madame de Montespan — although he had to have harboured suspicions when the testimonies that damned her were delivered to him. Having been accused of being a poisoner and Satanist, Montespan’s fate would surely be bleak in the court of a ruthless French king who would imprison people indefinitely in fortresses with meagre care just to keep the story quiet? We know that, by 1681, the king was persuaded of Montespan’s innocence in the matter and she remained in court, although she would not apparently be a sexual favourite nor receive his affections much thereafter — presumably, the love affair sullied by the accusations. Nevertheless, the streets of seventeenth century Paris were seemingly rife with occult practitioners of all types and variety, providing a powder keg of debauchery and devilry — and an incident that includes all the stereotypes of early modern witchcraft, Solomonic and grimoire magic, demonic pact, poison, love philtres, both low and high magic. There is so much to be said on this subject that this little piece barely touches the sides.

[1] Jacques Saint Germaine, Madame de Brinvilliers, 1970. [2] Anne Somerset, The Affair of the Poisons, 2004. [3] ibid. [4] ibid. [5] ibid. [6] ibid. [7] ibid. [8] ibid. [9] ibid.