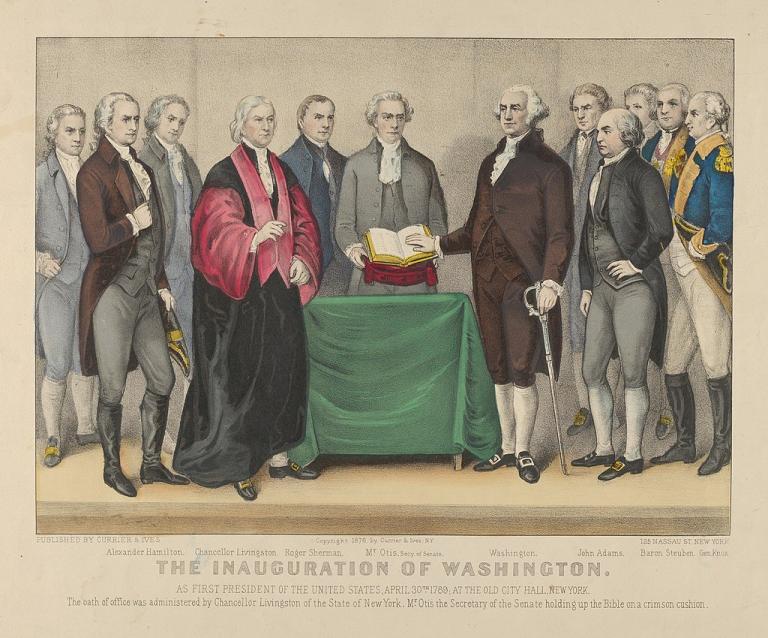

The Inauguration made me reflect on the importance of oaths, which were of enormous significance throughout history, a significance that I think has largely been lost today.

The moment Donald Trump became president was when he took the Oath of Office. Article II, section 1 of the Constitution says this of the president:

Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:–“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

National Catholic Reporter published an article by David B. Parker saying there is no evidence than George Washington added that. The story that he did was first told by Rufus Griswold in 1854, 65 years after the event. Parker says that the first president for whom we have good evidence that he added “So help me God” was Chester A. Arthur in 1881. Parker argues that the belief about Washington and the other presidents saying it emerged out of “Christian nationalism.”

Well, similar oaths are required for other public offices, members of the armed forces, and new citizens to this very day. Also for testimony in court and other legal transactions. The Wikipedia article on Sworn Testimony gives the wording required for use in courtrooms in different countries. In England, it’s this:

- I swear by [substitute Almighty God/Name of God (such as Jehovah) or the name of the holy scripture] that the evidence I shall give shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

In the United States, the God part may be left out, but some states, including California, still require it:

You do solemnly state that the testimony you may give in the case now pending before this court shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

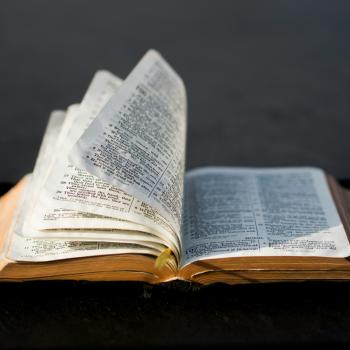

Most of the other examples given, including the mostly non-monotheistic India, include “so help me God,” or some other religious element. These generally reflect the practice of English Common Law, in which the oathtaker, holding a Bible or other sacred text, repeats the words, including “so help me God.” (See this and this.)

I suspect that Washington may have said “So help me God” by reflex if nothing more, something so commonplace that no one at the time thought it worthy of mention.

We know from his Farewell Address that Washington considered taking a legally-required oath to have religious significance. In his discussion of why “religion and morality are indispensable supports” to the American republic, he says this:

Let it simply be asked where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice?

For Washington, an oath cannot be relied upon unless the oathtaker feels a “religious obligation” to abide by it. For Washington, taking an oath in the name of God is the very point at which religion becomes foundational to civil government.

But many Christians too had problems with oaths. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said,

“Again you have heard that it was said to those of old, ‘You shall not swear falsely, but shall perform to the Lord what you have sworn.’ But I say to you, Do not take an oath at all, either by heaven, for it is the throne of God, or by the earth, for it is his footstool, or by Jerusalem, for it is the city of the great King. And do not take an oath by your head, for you cannot make one hair white or black. Let what you say be simply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; anything more than this comes from evil.” (Matthew 5:33-37)

Quakers in particular take that literally, as do some other Christians. So the Constitution and state laws allow for the word “affirm” to be substituted for “swear.” To say, “I affirm” that I will tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and leaving God out of it, rather than saying “I swear,” was thought to satisfy the letter of the Sermon on the Mount.

The Lutheran Formula of Concord, XII, 15, rejects the Anabaptist insistence “that a Christian cannot with a good conscience take an oath, nor with an oath do homage [promise fidelity] to the hereditary prince of his country or sovereign.”

Rather, the Augsburg Confession, Article XVI on Civil Affairs, says that “lawful civil ordinances are good works of God,” so that “it is right for Christians to bear civil office, to sit as judges, to judge matters by the Imperial and other existing laws, to award just punishments, to engage in just wars, to serve as soldiers, to make legal contracts, to hold property, to make oath when required by the magistrates, to marry a wife, to be given in marriage.”

Lutherans made the distinction between legal oaths, required by the magistrate, and frivolous, informal oaths. That the statement about oaths is followed by an affirmation of marriage reminds us that weddings, to this very day, involve taking a “vow,” which is a kind of oath.

Luther warns that breaking an oath made in God’s name, including the marriage vow, is a sin against the Commandment not to take God’s name in vain:

Therefore this commandment enjoins this much, that God’s name must not be appealed to falsely, or taken upon the lips, while the heart knows well enough, or should know, differently; as among those who take oaths in court, where one side lies against the other. For God’s name cannot be misused worse than for the support of falsehood and deceit. . . .

From this every one can readily infer when and in how many ways God’s name is misused, although it is impossible to enumerate all its misuses. Yet, to tell it in a few words, all misuse of the divine name occurs, first, in worldly business and in matters which concern money, possessions, honor, whether it be publicly in court, in the market, or wherever else men make false oaths in God’s name, or pledge their souls in any matter. And this is especially prevalent in marriage affairs, where two go and secretly betroth themselves to one another, and afterward abjure [their plighted troth]. (Second Commandment, Large Catechism, 51-53)

My impression is that we don’t take oaths as seriously as we used to, and as we should.

By the way, at the Inauguration, “so help me God” was not something added by the oath taker. Rather, the phrase was included in the wording given by the Chief Justice that the president-elect was supposed to repeat. So President Trump was not committing an act of “Christian nationalism” in saying those words.

Illustration: The Inauguration of Washington by Currier and Ives, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons