“Nature is beautiful because it comes to my eyes before death.” Kawabata Yasunari

Recently David Vernon, who has a new book on Japanese writer Yukio Mishima coming out soon, posted a comment on X (formerly known as Twitter) that I couldn’t agree with more: “Whatever we lose in translation, we lose far more by not reading at all.” It reminded me of an earlier article I wrote about my own literary journey years ago reading Latin American literature, and another post about the crucial service provided by translators. We are truly fortunate to see so many translated books flood the literary market.

One of my favorite spots for global literature is Japan. In the history of literature, there are certain trends that become famous. For example, nineteenth-century Russian literature (Tolstoy, Dostoevsky) or stories from twentieth century American Southern Gothic writers (Faulkner, McCullers, O’Connor, Morrison-to name a few).

I believe twentieth century Japanese literature is right up there in the history of literature. What makes it so special? Alan Transman points out that “Japanese literature clings to the concrete immediacy of the phenomenal world evoking the phantom quality of phenomena, the shadow of evanescence that hangs over all things” (Tansman, 5). There is enough realism in these books, hearkening back to the great novels produced in the nineteenth century, that grounds the stories, but also the twist of mystery that if we play close attention we encounter in our daily lives.

I spent a few weeks last year reading a lot of this literature before my family took a bucket list trip to Tokyo. In fact, I brought books by Japanese authors with me since I love to spend time reading while on vacation (thank you, Vanguard University’s O. Cope Budge Library). Like a good Bookstagrammar, I posted pictures when I visited some spots like the Tokyo Tower (feel free to scan the books from that time period).

We stayed in a quiet and quaint area in Eastern Tokyo (Kasai), located a few miles north of the Disneyland parks (message to the Disney adults out there: both parks were a lot of fun, and the Beauty and the Beast ride was AMAZING!). We did so much walking. The big attractions were nice, but it was the beauty and the peace of the local environment where we were staying that I think we all enjoyed the most.

My oldest son has been fond of Japanese culture since he was a child. His happy spot is the local koi pond in Torrance, California (or any koi pond, for that matter). He looks forward to the day when he can have a place with his own koi pond. He is the koi expert in the family. There are few things in life that are as calm as a koi pond and garden. On our trip, we spent a good amount of time just sitting by some ponds, observing the ambiance. We managed to stay by them for more than an hour.

My son just turned 14, and yet, he is the one often teaching me lessons about life. One of my biggest problems, if I may be a little self-conscious, is to simply stop and enjoy the beauty around me. To observe his simple joy of just sitting by the pond is a lesson of the value of quiet and peace that nature, in its proper setting, can provide. This was clearly something that came to him naturally, and I am happy that he knows from such a young age what brings him such joy.

Soaking in the phenomenal world is one of the key themes of Japanese literature. I am often drawn to the dialogue and relationships between the characters, but key moments of the plot are driven by events surrounding the environment often out of the control of the cast. In some cases, one is left in shock at what occurs.

I realized that in some sense the peace my son finds at a koi pond is the type I have reading a good book. Yes, reading is an activity, but it really is something that, at least for me, provides peace and rest. The pond and the book both beg for quiet and contemplation.

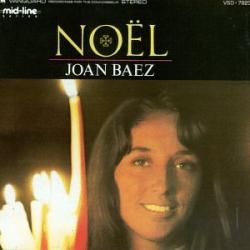

My son probably knows more Japanese than I do, so I am eternally grateful for the work of translators for making these books available. One of my favorite bookstores for Japanese literature is Kinokuniya (I go to the one that is found in the local Mitsuwa market). However, I was able to visit one of their bookstores in Tokyo, purchasing my first Haruki Murakami novel, Norwegian Wood (I always try to buy a book when I am on vacation). Murakami may be the most famous living Japanese novelist. All this talk about Japanese literature and book stores, but I have failed to discuss my favorite author.

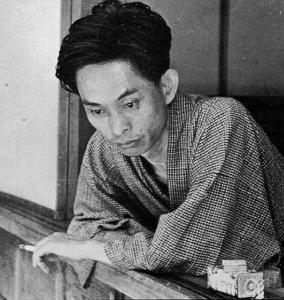

From my readings, the standout writer is Japan’s 1st Nobel Prize winner in Literature in 1968, Kawabata Yasunari (some say it should of went to Mishima who had been nominated throughout the 1960s). His book Snow Country is filled with countryside imagery that symbolizes the twist and turns of the relatively short novel. At the heart of his books that I have read is complicated relationships and family legacy.

My relationships with books, frankly, are not complicated. Sometimes a certain writer just strikes a chord. Both Snow Country and another one of his novels Thousand Cranes were two books I could just not put down. I read both within days because the plotting and style of Kawabata’s writing is just that good. They are relatively short so they are a nice place for an introduction to Japanese literature. Tansman declares this about Kawabata’s surrealistic style: “His gift to world literature was a set of sensual, erotic, strange, dreamlike-but-gritty short stories and novels—at once magical and realistic” (Tansman, 71). Do not let the language of surrealism scare you off—the minute you meet the protagonist on the train of Snow Country, you are immediately invested in this story of a tragic love affair.

The family gave me one “nerd” day, a day away from the ponds and amusement parks, and I used it to stop by the Natsume Sōseki Memorial Museum since it was local enough that we did not get too off of our path. My wife Lluvia took this picture of me by Sōseki’s bust. He is considered the father of modern Japanese literature so I wanted to stop by and pay homage to him since he started this literary legacy. I had a chance to read his tragic novel Kokoro right before the trip.

Tansman writes the following about Sōseki: “In literature, he stands inimitable, a towering figure whose genius chanced to manifest itself at a time of extraordinary cultural and political transformation” (Tansman, 65). The great writers following Sōseki (Kawabata, Mishima, and Ōe, to name some of my favorite) struggled with this legacy, reacting to the political whirlwinds of twentieth century Japan. I would love to see more historical studies of these figures come out soon.

One of these days I hope to return to Japan. We receive many questions about how we enjoyed our trip. Of course, there were many aspects of it we all liked. But the common thing, whether it was by a pond or reading a short novel, was we found a place to rest.