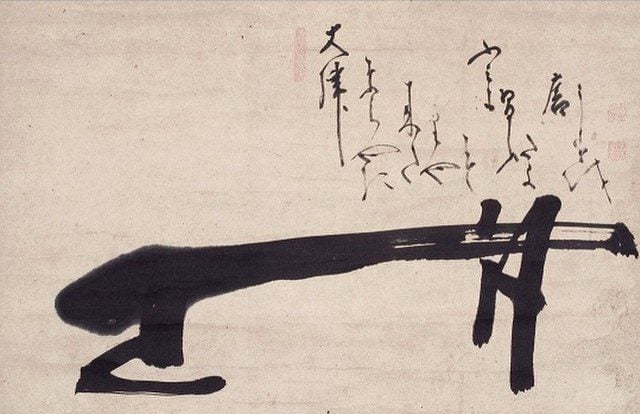

Hakuin Ekaku

(between 1686 & 1769)

(Maurine Mo Weindhardt is a Dharma Holder with the Empty Moon Zen Sangha. She delivered this talk at our December Rohatsu retreat. I asked her if I could reprint it here, and she graciously agreed.)

For those of you who might need a sincere reminder, hear me. This is a deep and abiding truth: You are worthy. You are sacred. You are loved.

Today, we’re going to talk about meeting the struggle. This has many meanings — but whether big or small, minor, or utterly life-changing, the struggle is real. I wonder, what might yours include in this moment?

Zen is a practice of attention. Of awakening to the habits of our minds and actions, and cutting through the delusions of our ego-driven narratives. Basically, cutting through our own bullshit. Not just seeing — but experiencing, fully, the intimate interconnectedness with all that is. Experiencing the bright, boundless emptiness, where concepts of self and other fall away — where there truly is nothing but this, and then remembering this, realizing this, in the thick of everyday life. Bringing this awakening into every moment.

Easy, right?

What we’re really talking about is just the stuff of our regular, mundane, bread & butter, everyday lives. The joys and pitfalls of being human, where we’re often reacting and trying to make sense of ourselves and the world. Perhaps trying to heal. Trying to exert control. Trying to find certainty, craving the comfort and assurance that brings.

The question I’d like you to hold through this talk is, “What is the ground of my practice?”

We’ll begin by exploring this question through the lens of a koan — a Zen encounter from long ago. A story in which we’re invited to recognize the aspects of ourselves in each character. I’ll read the koan first, and then give some context around what led up to this thundrous encounter:

Case 23 of the Gateless Gate: Neither Good Nor Evil

The 6th Chinese Ancestor Hui-neng was pursued by Ming, the head monk, as far as Ta-yu Peak. Hui-neng, seeing Ming coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, “This robe represents the Dharma. There should be no fighting over it. You may take it back with you.”

Ming tried to lift it up, but it was as immovable as a mountain. Shivering and trembling, he said, “I came for the Dharma, not for the robe. I beg you, lay brother, please open the Way for me.”

Hui-neng said, “Don’t think good; don’t think evil. At this very moment, what is the original face of Ming the head monk?”

In that instant Ming had great satori. Sweat ran from his entire body. In tears he made his bows, saying, “Besides these secret words and secret meanings, is there anything of further significance?”

Hui-neng said, “What I have just conveyed to you is not secret. If you reflect on your own face, whatever is secret will be right there with you.”

Ming said, “Though I practiced at Huang-mei with the assembly, I could not truly realize my original face. Now, thanks to your pointed instruction, I am like someone who drinks water and knows personally whether it is cold or warm. Lay brother, you are now my teacher.”

Hui-neng said, “If you can say that, then let us both call Hung-jen our teacher (the 5th Chinese Ancestor). Maintain your realization carefully.”

To fully appreciate this encounter, you need the story behind this story, of why Head Monk Ming was chasing Hui-neng in the first place.

Hui-neng, who became our 6th Chinese Ancestor, was born in the year 638. His father died when he was young. Hui-neng had no education, and as a kid he sold firewood to support himself and his mom. One day he heard a monk reciting the Diamond Sutra, and experienced deep realization. When asked, the monk told him his teacher was Hung-jen, who lived over 1,000 miles away at a temple in North China.

A neighbor kindly agreed to support his mother, and Hui-neng set off to find Hung-jen. After their first encounter, Hung-jen saw the worth in this new student, and assigned Hui-neng to husk rice in the harvesting shed.

Many months passed, and Hung-jen felt the need to name a successor. To determine who his successor would be, he announced a contest, inviting anyone who thought they were worthy of transmission to submit a poem showing their understanding of the Way. The author of the most insightful, penetrating poem would receive transmission and become the next master.

This temple had over 700 monks, and they all felt that the leader of their assembly, Shen-hsiu, had the clearest insight — so none of them wrote anything. Shen-hsiu, however, was not sure of his own attainment. Instead of turning in a poem, he wrote one anonymously on a wall, figuring that if it was approved, he would step forward and announce that he was the author; if it were disapproved, he could just keep quiet.

On this wall, Shen-hsui wrote:

“The body is the Bodhi Tree;

The mind is like a clear mirror;

Moment by moment, wipe the mirror carefully;

Let there be no dust upon it.”

Hung-jen praised this poem and had all of the monks commit it to memory. However, he did not say anything about making its author his successor.

Hui-neng, our young, penniless, unschooled lay practitioner, did not learn about the contest until he heard a monk reciting Shen-hsui’s poem. Since he didn’t know how to write, he asked an acolyte to write his response on the wall beneath. It read:

“Bodhi really has no tree;

The mirror too has no stand;

From the beginning there’s nothing at all;

Where can any dust alight?”

Though everyone was impressed with this second poem, it caused quite a disturbance when the monks discovered it was written by a nobody layman working in the harvest shed.

However, the teacher Heng-jen immediately recognized the worth of this poem, but rubbed it off the wall with his slipper, claiming it was of no value. That night however, he summoned Hui-neng to his room and preached on the Diamond Sutra. Hui-neng grasped the inner sense of the sutra at once, and without hesitation, Heng-jen conveyed the robe and bowl of Bodhidharma to him as symbols of transmission.

The teacher then warned Hui-neng that jealous monks would try to harm him if he stayed at the monastery. To protect him, Heng-jen personally rowed Hui-neng across the river and advised him to polish his realization secretly for some time before emerging as a teacher. This is how Hui-neng received transmission.

The next day, all of the monks found out what had happened, and needless to say, they were pissed. They were certain that their old teacher had made a mistake. They set out in pursuit of Hui-neng to bring back the precious symbols of transmission.

The head monk, named Ming, was a former general with a powerful body and will; he quickly outpaced and outdistanced the other monks, tracking Hui-neng through the mountains. This is where we pick up the main case of the koan.

Hui-neng, seeing Ming coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, “This robe represents the Dharma. There should be no fighting over it. You may take it back with you.”

This rocked Ming to his core.

Ming tried to lift it up, but it was as immovable as a mountain. Shivering and trembling, he said, “I came for the Dharma, not for the robe. I beg you, lay brother, please open the Way for me.”

Hui-neng said, “Don’t think good; don’t think evil. At this very moment, what is the original face of Ming the head monk?”

Original face can also be translated as True Self. What is the True Self of Ming the head monk?

In that instant Ming had great satori. Sweat ran from his entire body. In tears he bowed, saying, “Besides these secret words and secret meanings, is there anything of further significance?”

Hui-neng said, “What I have just conveyed to you is not secret. If you reflect on your own face, whatever is secret will be right there with you.”

Ming said, “Though I practiced at Huang-mei with the assembly, I could not truly realize my original face. Now, thanks to your pointed instruction, I am like someone who drinks water and knows personally whether it is cold or warm. Lay brother, you are now my teacher.”

Hui-neng said, “If you can say that, then let us both call Hung-jen our teacher. Maintain your realization carefully.”

In so many ways, each of us is the head monk Ming. Certain. Righteously judgemental. Rigidly convinced of our opinions and views. Angry (or sometimes, more insidiously, disappointed), with those who fail to align with what we consider right or wrong; good or evil; and willing to impose our views violently, if need be.

Sometimes the violence of certainty and knowing is physical in nature; but what I really want to underscore for this group is the verbal and emotional violence we can be so prone to. All the many flavors of, “I think you should act differently, feel differently, or be other than you are, and here’s why I’m right and you’re wrong.”

I wonder – in how many different ways have you been head monk Ming? Judging and perhaps descending on someone you think is in the wrong, to berate them or straighten them up? Or, how many times have you simply fantasized about doing that?

In yesterday’s dharma talk, Tom mentioned that a 10 year old boy decked out in a bright red Trump hat and American flag backpack was on our flight to Seattle. In an instant, I had that first mind of head monk Ming — how dare the adults in his life brainwash this boy to idolize and essentially advertise for a crude, narcissistic, convicted con man who gets off on lying, sexually abusing women, disrespecting and belittling others, and blah blah blah… (It builds up steam fast, doesn’t it?) The list was loooong. It was surprising how quickly these vitriolic judgements spewed from my brain, and contorted my face. And at exactly that moment, this 10 year old boy happened to lock eyes with me, and smile. In that moment, I noticed what was happening in my mind, and what it was doing to my face, and I saw my mental formations clearly for what they were. (Breathe)

An opening of my heart; a relaxing of my judgments; I smiled back, enjoying a brief moment of connection with this boy, who is not me, and yet we are the same.

Now, for an important turning of this koan. Beyond how we treat other people — as critical as that is — we must equally examine how we treat ourselves. Shine light on this with me for a moment. In how many different ways have you been head monk Ming, descending upon yourself? Judging and berating yourself for being wrong, for making a mistake, because “you should have blah blah blah”?

My god are we good at “shoulding” all over ourselves. In my experience, we are rarely as brutal with anyone else in the world as we are with ourselves. All the things we regret or wish we’d done differently, and refuse to forgive ourselves for — where is our compassion then? How readily do we suffocate ourselves from the very thing we aspire to practice for all beings?

We would never allow someone to treat a friend or loved one the way we can treat ourselves sometimes — and yet for some reason, it can feel acceptable to unleash this unforgiving bludgeon upon ourselves. If this rings true for you, as it does for me, it is worthy of deep reflection.

This version of my head monk Ming came up earlier in the week. I won’t get into all the details, but in a nutshell I encountered a seething white-hot angry 17-year-old Mo who had a middle finger for everyone — especially for now-me. That younger self tracked me down through the mountains of my mind, across time and space, and absolutely tore me apart. She blamed me for so many things, including my mom’s death, and she beat me bloody with all of the ways that that part of me was certain that what I did was either wrong or not enough.

I should have done this and that; if only I’d said such & such, or not done whathaveyou, everything would have been different. Oh, such imaginative mental formations… It was brutal.

Whether descending on others, or descending on yourselves, I’m sure that all of you have your own versions of an angry and certain head monk Ming.

And this is where I invite us to explore the aspect of ourselves that is Hui-neng in this koan, and return to my original question at the beginning of this talk:

“What is the ground of your practice?”

Zen permeates every aspect of my life. I don’t always pay as much attention as I wish, or sit zazen as consistently as I want to, but everywhere I turn, there’s my practice. Just like every step I take, there I am. Same ol’ me. This wildly imperfect being. A regular, flawed person, who just happens to have committed to prioritizing awakening and compassion — to seeing the bright emptiness we all share, regardless of form, as often as I can. And maybe that’s the point.

Hui-neng, seeing Ming coming, laid the robe and bowl on a rock and said, “This robe represents the Dharma. There should be no fighting over it. You may take it back with you.” Ming tried to lift it up, but couldn’t.

In this moment, Ming’s enraged, ego-centered self was at once completely smashed. He saw through his certainty, his misguided and harmful actions, and it broke him wide open.

Shivering and trembling, Ming said, “I came for the Dharma, not for the robe. I beg you, lay brother, please open the Way for me.”

Hui-neng said, “Don’t think good; don’t think evil. At this very moment, what is the original face of Ming the head monk?”

At this very moment, what is your original face? What is your true nature? What is the ground of your practice? You’re up a tree, dangling from a branch by your teeth. Say something.

Buddha Nature neither rejects nor embraces. It’s vibrantly alive in just this, whatever “this” might be. It does not assess worthiness; it does not play favorites. It does not pat you on the head and reward you for being “good”; nor does it punish you or withhold itself when you act “bad”. It is not transactional; it does not function within the dualistic constraints of good or evil, right or wrong, better or worse, enough or not enough. Buddha Nature pervades the whole universe, existing here and now; everything you see, everything you hear, is in fact ‘it’. ‘It’ cannot be confined or reduced into arbitrary categories of worth. Buddha Nature does not make value judgments. We do that.

It’s hard not to think of good and evil; to divide the world, other people, or myself into classifications of good and bad, right and wrong. I mean, critical thinking is a necessary skill in the world of form, it allows us to make decisions, anticipate risks and dangers, and hopefully to feel our way into more consistently living our values. The catch is holding our judgments loosely; being aware and cautious of the trappings of knowing, or tightly-held certainty.

As written in the Hsin-hsin ming, or the ‘Precepts of the Faith’: “To set up what you like against what you dislike — this is the disease of the mind.”

We all grapple with the stickiness of certainty, setting up what we like against what we dislike. But regardless of the particulars or the circumstances, how we treat each other — and how we treat ourselves — matters. When the ground of practice is compassion, for ourselves and all beings — when the illusion of separation falls away and the egocentric self is at once completely smashed — this is a great gift of awakening.

The invitation is to recognize this functioning in the thick of activity. Can we realize this in the face of intense emotions? In the face of a wounded heart, or a body that’s in pain? When getting laid off, or when rudely honked at in traffic?

We each must earn our realizations — our wisdom. There are no shortcuts. This goes beyond conceptual understanding — awakening cannot be learned, it must be lived. And it requires continuous effort.

It’s a dark fucking world in so many ways. And yet. In my experience, with each decision, each loving or thoughtful action we take, things change for the better in ways we don’t always see — slowly but surely bending the world towards compassion. Towards kindness. Towards love.

We wear these bodies, these forms, forgetting that we are not them. Like a bead of ocean spray, momentarily a separate droplet, forgetting the source that it’s part of, that it is in fullness, even as it careens back towards the boundlessness from which it came.

The whole is never separate from the particular; the particular is never distinct from the whole. Awakening to this truth changes everything (& nothing at all) in an instant. And this truth is not to be found outside of ourselves, outside of this moment, outside of the infinite just this.

The Buddha taught that we’re already awakened — there’s nothing to seek, nothing to gain or lose, nothing to obtain. It’s just a small matter of not picking and choosing — of not taking too seriously what we like or dislike. This doesn’t mean to have no wants or fears or desires — that’s impossible. These are natural functions of our human mind. It means practicing to see them clearly for what they are — stories, mental formations, empty mind bubbles — so they don’t sway our actions towards the small or the selfish. So we can see that shared light in all beings — even when they piss us off, or worse.

This treasure already shines brightly in each one of us tiny droplets. Nothing is missing. Do you understand? Good, that’s a start, but understanding isn’t it. This isn’t an intellectual exercise. Realize this for yourself. Explore this for yourself. Like Ming, be someone who drinks water and knows personally whether it is cold or warm. Realize that to which words can merely point.

To use different language, we are each God waking up to and recognizing God within and all around. I – thou – all – art sacred. Nothing is left out. Consider the implications of this.

Zen is a practice of attention. Of awakening to our habits, and cutting through our own bullshit. Of fully experiencing this intimate, sacred interconnectedness — the bright, boundless emptiness, where concepts of self and other fall away — and bringing this awakening into the thick of everyday life.

Easy, right?

The struggle is absolutely real. And it can be absolutely brutal. And just as real, is the joy, the effort, the love, the community, the practice of compassion, the mutual support. You’re already home. The Way is already before you. Even as a distinct droplet, you are the entire ocean. And so are “they”, whoever you consider “they” to be.

Our invitation is to be intimate with just this, meeting whatever this might be, with the strength of Hui-neng, standing the ground of his practice, hand in hand with the strength of head monk Ming, willing to break open completely.

What I have just conveyed to you is not secret. If you reflect on your own face, whatever is secret will be right there with you. What you seek is within, and it is yours alone to give. Where can any dust alight?”

Please — maintain your realization carefully.

Thank you.