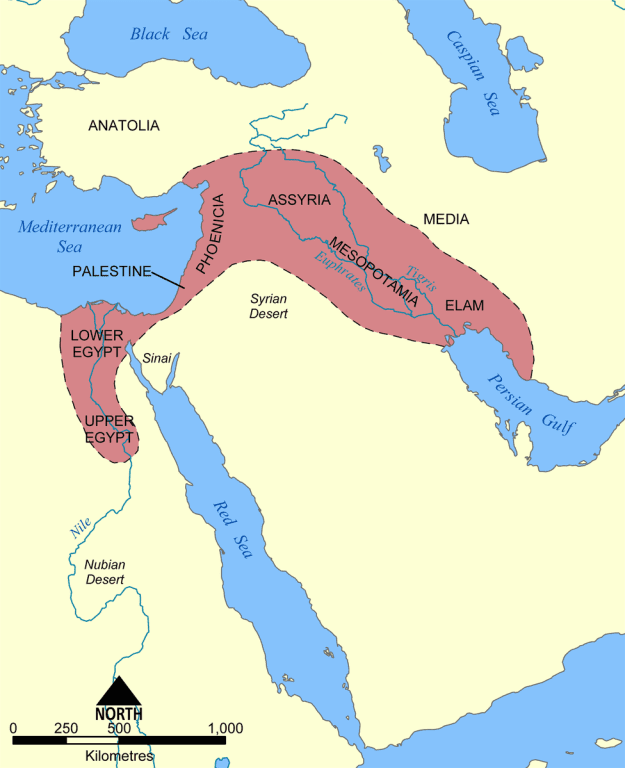

The Hebrew “Northern Kingdom” — often called Israel or, after its eventual capital, Samaria — was formed in the tenth century before Christ when the ten northern tribes rebelled against the political entity headquartered in Jerusalem, which thereupon came to be called the “Southern Kingdom,” or the Kingdom of Judah. But, after a three-year siege of Samaria, the Northern Kingdom was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 722 BC. The Assyrian kings Shalmaneser V, Sargon II, and Sennacherib deported many of the residents of Israel to the areas that are known today as Syria and Iraq. There, the exiles were forced to work as agricultural laborers on farms that were owned by the king or other high officials or by the temples, and, over time, they were assimilated into Assyrian language and culture. (Some Israelites remained behind in the former Northern Kingdom, where they became known as “Samaritans.”) The disappearance of the people of the Northern Kingdom gave rise to the concept of the “Ten Lost Tribes.”

The conquest of Israel (and of adjacent Syria) was part of the long-term expansion of a number of succeeding states within the region of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and then out of that region. They expanded out of Mesopotamia, the area “between the rivers,” up and over the top of the Fertile Crescent and then down southward toward Egypt, the other great Middle Eastern power of the day.

At the beginning of the sixth century BC, a large number of Judeans — mostly residents of city of Jerusalem — were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which had succeeded the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Neo-Babylonian relocations occurred in several waves, beginning with probably about 7000 exiles after Nebuchadnezzar II’s siege of Jerusalem in 597 BC. They continued with further deportations (of indeterminate numbers of exiles) in the wake of the destruction of Jerusalem and the razing of Solomon’s Temple in 587 BC and again in 582 BC. These deportations created what is commonly referred to as “the Babylonian captivity.” Anticipating the conquest and the forced exiles, and under divine inspiration, the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi and his small party voluntarily fled Jerusalem southward, away from Mesopotamian imperialism and eventually to the New World.

The actual conquest of Egypt by the Achaemenids, who had succeeded the Neo-Babylonians by then as the rulers of Mesopotamia, occurred during the sixth century BC.

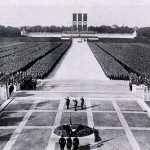

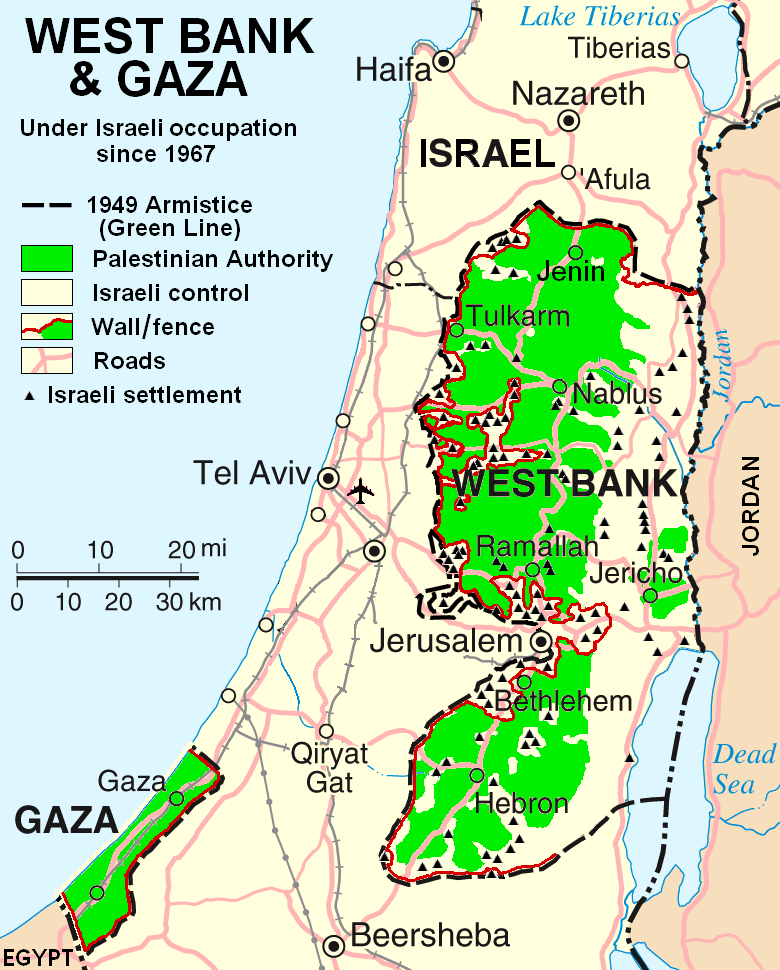

I was immediately (and uncomfortably) reminded of the enforced exile of the peoples of the northern and southern Israelite kingdoms when I heard about President Trump’s suggestion that the best solution to the current problem of Gaza would be to simply empty out the people who live there and then to distribute them between Jordan and Egypt. (See, for example, National Review: “Trump Floats Plan to ‘Clean Out’ Gaza, Send Palestinian Refugees to Jordan, Egypt” If you can’t access the National Review article, I’m confident that there are plenty of other places online where you can read about Mr. Trump’s proposal.) It would be, in the most literal sense of the explosive term, a kind of “ethnic cleansing.”

I was also reminded of the infamous Munich Agreement — aka the “Munich Betrayal” — that was signed in 1938 between Germany’s Adolf Hitler, Italy’s Benito Mussolini, France’s Édouard Daladier, and Great Britain’s Neville Chamberlain. In hopes (on the parts of Chamberlain and Daladier, at least) of avoiding war, the signatories agreed to allow Nazi Germany to annex the Sudetenland, a German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia. Strikingly and (to my mind) arrogantly, Czechoslovakia was not represented at the meeting in which the Munich Agreement was worked out and the fate of the country was decreed. And, of course, catastrophic war came anyway.

Although Gaza was already an overcrowded, poor, and unpleasant neighborhood long before the recent Israeli incursion into it, and even before the loathsome ascendancy of Hamas over it, I would be enormously surprised if the people of Gaza would willingly be uprooted and handed out to other nations. As the late Achilles might have said, it’s a poor place, but it’s theirs. Furthermore, although the people of Gaza are Arabs, Arabs aren’t fungible. They’re not mutually interchangeable, any more than — merely because they all speak English and share traditions like the common law — Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, and Oregonians are interchangeable. Palestinians aren’t Egyptians or Jordanians, let alone Iraqis, Algerians, Tunisians, or Moroccans. They have their own distinct culture and their own very distinct dialect. Indeed, on account of the prolonged separation between them, the Palestinian colloquial Arabic of Gaza has even begun to diverge from that of the West Bank. And families within Gaza intermarry, as do West Bank families. But, because they simply can’t, residents of Gaza and residents of the West Bank seldom socialize with each other, let alone marry each other. They are growing apart.

And would Jordan really welcome them? Jordan has already experienced stress between its deep-rooted Jordanian natives, who tend to dominate the police and the military, and its multi-generational but still relatively recent Palestinian refugee population, who are disproportionately successful in business and education. (It’s probably not purely coincidental that King Abdullah of Jordan married a Palestinian — although the fact that Queen Rania is extremely beautiful probably helped the medicine go down.) How many more hundreds of thousands of Palestinians could Jordan readily assimilate?

And would Egypt welcome an influx of hundreds and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians? The country is already overcrowded and poor. Furthermore, it has faced challenges from radical native-born Islamic fundamentalists for many years (since long before the dramatic assassination of Anwar Sadat by members of an Islamist cell) and allowing remnants of Hamas to enter its territory, as they surely would, would almost certainly threaten its stability.

But what bothers me most about Mr. Trump’s proposal is the sheer master-of-the-universe arrogance of it. I’m hoping that it was nothing more than a casual off the cuff remark, rather than a serious policy suggestion. I’m reminded of the mid-level Foreign Office bureaucrats in London after World War One — the Great War, remember, “the war to end all wars” — who, it is said, drew up some of the boundaries of newly-invented countries in the Middle East using only a straight-edge and a pencil. They had absolutely no first-hand knowledge of the Middle East and, being classics graduates of Oxford and Cambridge, not much book-learning about the area. (Having read Xenophon’s Anabasis in the original Greek just doesn’t quite cut it.)

I’m trying to avoid politics here. Especially on the Sabbath. But I felt that, since I’m a sometime observer of the Middle East, this was one topic upon which I couldn’t really avoid commenting.

Posted from Bountiful, Utah