Infallible Ecumenical Councils; Nature of Saints’ Intercession

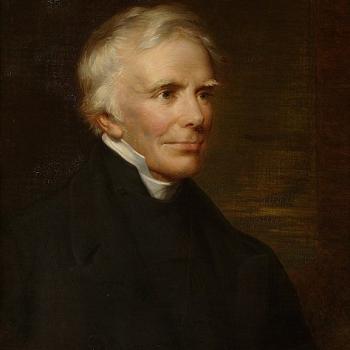

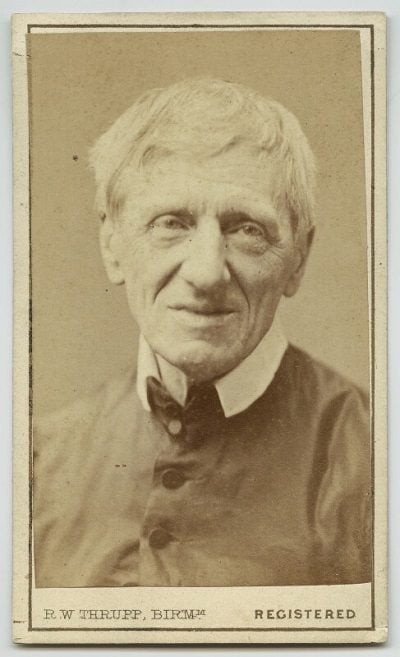

Edward Bouverie (E. B.) Pusey (1800-1882) was an English Anglican cleric, professor of Hebrew at Oxford University for more than fifty years, and author of many books. He was a leading figure in the Oxford Movement, along with St. John Henry Cardinal Newman and John Keble, an expert on patristics, and was involved in many theological and academic controversies. Pusey helped revive the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Church of England, and because of several other affinities with Catholic theology and tradition, he and his followers (derisively called “Puseyites”) were mocked by over-anxious adversaries in 1853 as “half papist and half protestant”. But, unlike Newman and like Keble, he never left Anglicanism.

I continue my replies to Pusey by examining a few portions of his Eirenicon, Pt. III, entitled, Is healthful reunion impossible?: a second letter to the Very Rev. J.H. Newman, D. D. (London: Rivingtons, 1870). He described Newman in the beginning of his second volume of three, as his “dearest friend” and a person “whom I still admire as well as love” and he fondly recalled the “sunny memories” of their time together in the Oxford Movement. Pusey’s words will be in blue. All of my replies to Pusey will be collected under the “Anglicanism” section of my Calvinism and General Protestantism web page, under his name. I use RSV for Bible citations.

*****

In principle I agree, that upon any point which a General Council, received by the whole Church, should pronounce to be “de fide,” private judgment is at an end. Private judgment has no place there. It is for the Church to decide upon the evidence, whether from Holy Scripture or from unbroken tradition from the first. She, not individuals, is the judge of that evidence ; for she, not individuals apart from her, has our Lord’s promises. Whatever she should decide, I should not only accept, but it has long been my habit of mind, “implicite” to accept it beforehand. I mean that, while of course I believe all which I know that the Church has defined, I believe, with my inmost will, whatever she holds, whether I know it or no. . . . if the whole Church, including the Greek and Anglican Communions, were to define these or any other points, to be “de fide,” I should hold all further inquiry as to evidence to be at an end. In whatever way they should rule any question, however contrary to my previous impressions, I should submit to it, and hold it, as being, by such universal consent of the whole Church, proved to be part of the Apostles’ faith. I have ever submitted my credenda to a power beyond myself. We have differed, then, and must differ, upon a point of fact— what are the component parts of that Church, whose reception of any doctrine saves us from all further inquiry, and rules that doctrine for us; not as to the principle, whether any such power exists. (pp. 3-4)

In regard to the office of the Church, and the consequent duties of individuals towards her in the abstract, the Council of Trent and the Church of England are, I am persuaded, agreed. Both Churches hold and must hold, what Holy Scripture teaches, that the Church is “the pillar and ground of the truth;” both agree that she has the office to transmit, guard, preach, propagate that God-given truth ; both must hold, that what has once been infallibly fixed cannot receive any additional certainty (since nothing can add to infallibility), and so, that with regard to all which has been fixed by (Ecumenical Councils, the office of the Church is only to transmit and teach it. Later (Ecumenical Councils did not add authority to the earlier, but entered on their office by the confession of what had been laid down by those before them. (pp. 21-22)

The Church, not individuals, must be the judge, whether what she proposes as ” of faith” does rest on that tradition. (p. 23)

This conception of sublime Christian authority is consistent with the Catholic rule of faith, and most emphatically not with sola Scriptura, which denies the infallibility of ecumenical councils. Catholics would disagree, however, with the inclusion of official Anglicanism as a full participant in such a council. There was enough disagreement to preclude such a council in 1870, and there is far more now, as Anglicanism continues to reject apostolic teaching (especially in the area of morals) in several serious ways.

On the crucial question of ” the Invocation of saints,” the Lutheran Abbot of Lokkum [Gerhard Wolter Molanus: 1633-1722] asked . . . for a recognition of the principle, which many of your writers have laid down, that, even when things are asked directly of the saints, nothing more is intended than by the simple “Ora pro nobis” [“pray for us”]. He wished it to be stated, that whatever be the language employed, they are not asked as though it were in their own power to grant any thing, but only to pray our Lord with us, that He would grant it. The Lutheran’s proposition was —

If the Roman Catholics say publicly that they have no other trust toward the saints, than that which they feel towards the living, whose intercessions they implore; that they understand all and each of the prayers directed to them, in what words or forms soever conceived, no otherwise than intercessionally, — as when they say ‘Sancta Maria, libera me in hora mortis’ the meaning is, ‘Holy Mary, intercede for me with thy Son, that He free me in the hour of death,’ — the peril alleged by Protestants as to the Invocation of Saints will cease. If, moreover, the Romans from time to time teach their people that the Invocation of Saints is not simply enjoined, but by the force of the Council of Trent is placed at every one’s choice, whether he would direct his prayers to the saint or to God Himself; that the saints ought not to be invoked rashly and needlessly on every occasion, . . . (pp. 15-16)

This was always the case in Catholic theology — the claim otherwise derived from a miscomprehension of non-literal sorts of language in Catholic descriptions and pious expression, as I have dealt with in previous installments of this series. We have already made this clear “publicly” in the Council of Trent, in its last (25th) session in December 1563, in its Decree, On the Invocation, Veneration, and Relics, of Saints, and On Sacred Images, where it is stated that “the saints, who reign together with Christ, offer up their own prayers to God for men” and that “it is good and useful suppliantly to invoke them, and to have recourse to their prayers, aid, (and) help for obtaining benefits from God, through His Son, Jesus Christ our Lord, who is our alone Redeemer and Saviour.”

None of this remotely teaches or even implies the saints have power in and of themselves to answer prayers. The whole point is that their prayers have more power and efficacy, due to their perfect holiness (Jas 5:16). One wonders, then, “where’s the beef?” Why was Molanus asking a question that had plainly been addressed at Trent? What is there not to understand? Pope Pius IV’s Tridentine Profession of Faith of 13 November 1564 reiterates that the saints in heaven “offer prayers to God for us” (Denzinger #1867; p. 436 in the 2012 43rd edition).

Principles so enunciated would remove most of the objections which lie so deep in the English mind (such, I mean, as are not members of the Roman Church, whether members of the English Church or Dissenters), against the invocation. This would remove what has been the special crux to many of us. (pp. 19-20)

Again, I don’t see how Trent and the Tridentine Profession of Faith were not crystal clear on this point. That’s the magisterium and the “presupposition” for how any writings of Catholic individuals on the topic are to be understood. If we supposedly taught otherwise, then I think Pusey and any other Protestant critic ought to — and would be able to — produce statements along those lines from official sources like popes and ecumenical councils. Instead, typically, we get endless excepts from Liguori’s Glories of Mary, which, as I explained years ago, are habitually taken out of context and presented in a half-truth fashion, ignoring other relevant excepts from the same book that fully explain their meaning. It’s like Protestants who do this are sawing off the limb they are sitting on or creating their own difficulties, where in fact there are none.

*

***

*

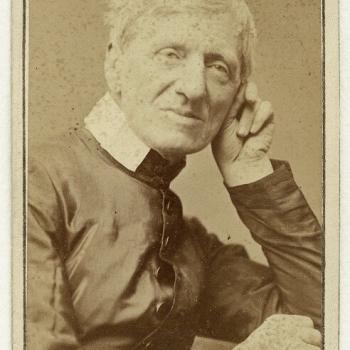

Photo credit: photograph of St. John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) from 1866, four years before E. B. Pusey’s second long letter to him. [public domain]

Summary: Reply to a few portions of E. B. Pusey’s Is healthful reunion impossible?: a second letter to the Very Rev. J.H. Newman (1870), dealing mostly with the intercession of the saints.